Gary Mitchell seems at first an unlikely playwright to have play produced in the Irish language. But such is the cultural dividend of the peace process that a Protestant from Rathcoole now sees his work translated expertly by Andrea Higgins and produced by Belfast-based theatre company Aisling Ghéar. Their production of Love Matters at Project Arts Centre gives parity of esteem to both languages: providing headsets and a simultaneous translation to any audience member who wanted one, thus opening up the audience beyond the usual Gaeilgeoir contingent. This is to be welcomed and would go a long way to removing the hesitation many people have over attending a production in Irish.

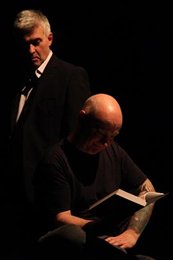

Set in mid-1990s Northern Ireland, Love Matters opens in a grimy prison cell. Big Ernie is your standard-issue banged-up loyalist hardman, complete with heavily tattooed arms and balding shaved head that looks like it has come in contact with a few batons in its time. He trusts Darren (Diarmaid Murtagh) to keep an eye on his wife Julie (Tara Breathnach) and son Wee Ernie (Piaras Donnelly) while he is in prison. Darren’s failure as an enforcer is Brad’s (Cillian Ó Gairbhí) opportunity, and Julie and he are engaged in what seems like a suicidal tryst. Wee Ernie is none too pleased about this, but he is more preoccupied with getting his dad to like him when he finally meets him again after their years apart, than he is with his mother’s affair. Meantime, Brad’s parents, hard-bitten detective Henry, played by Nollaig MacAodha and his alcoholic mother, Sadie played by Carina MacLeod, try to employ a variety of clumsy strategies to end their son’s affair with Julie, revealing their own mixed motives for doing do in the process.

Set in mid-1990s Northern Ireland, Love Matters opens in a grimy prison cell. Big Ernie is your standard-issue banged-up loyalist hardman, complete with heavily tattooed arms and balding shaved head that looks like it has come in contact with a few batons in its time. He trusts Darren (Diarmaid Murtagh) to keep an eye on his wife Julie (Tara Breathnach) and son Wee Ernie (Piaras Donnelly) while he is in prison. Darren’s failure as an enforcer is Brad’s (Cillian Ó Gairbhí) opportunity, and Julie and he are engaged in what seems like a suicidal tryst. Wee Ernie is none too pleased about this, but he is more preoccupied with getting his dad to like him when he finally meets him again after their years apart, than he is with his mother’s affair. Meantime, Brad’s parents, hard-bitten detective Henry, played by Nollaig MacAodha and his alcoholic mother, Sadie played by Carina MacLeod, try to employ a variety of clumsy strategies to end their son’s affair with Julie, revealing their own mixed motives for doing do in the process.

The set consisted of four purpose-built paint splashed edifices, placed at intervals upstage; these served cleverly as offstage space, prison walls, street corners, walls and doorways. Each of the structures had long strips painstakingly cut from top to bottom giving them the look of New York skyscrapers at times. The cut out strips were backed by gauze and occasionally dimly lit from behind, but the lighting potential of this set up was not exploited fully. Set designer David Craig and set builder Seán MacSeáin went to a lot of trouble to render an effect that was barely used.

Love Matters is a tale of loyalty and betrayal with a simple moral compass: actions have fairly predictable consequences. The characters function as plot devices to drive the storyline to its melodramatic conclusion. Despite the shoulder-shrugging predictability of the ending, the build up to it lacks much of a sense of foreboding: it is more farcical accident than engaging thriller.

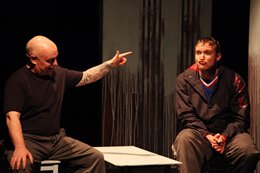

Gary Mitchell’s skill at dialogue is at its best in the blackly humorous exchanges between Darren and Wee Ernie. Darren, in a panicked attempt to make up for his years of failure, tries to turn the mildly rebellious young lad into a killing machine overnight. Directors Bríd Ó Ghallchóir and Tony Devlin have delivered a show in which the acting style of most of the performers was low-key and realistic. A notable exception is Diarmaid Murtagh’s playing of Darren. The fumbling, would-be enforcer is played with a comic intensity and clownish physicality that, while effective, looks like it belongs in another play. The character of young Ernie is the most subtly drawn of all and engagingly played by Piaras Donnelly.

Gary Mitchell’s skill at dialogue is at its best in the blackly humorous exchanges between Darren and Wee Ernie. Darren, in a panicked attempt to make up for his years of failure, tries to turn the mildly rebellious young lad into a killing machine overnight. Directors Bríd Ó Ghallchóir and Tony Devlin have delivered a show in which the acting style of most of the performers was low-key and realistic. A notable exception is Diarmaid Murtagh’s playing of Darren. The fumbling, would-be enforcer is played with a comic intensity and clownish physicality that, while effective, looks like it belongs in another play. The character of young Ernie is the most subtly drawn of all and engagingly played by Piaras Donnelly.

Mitchell’s own experiences as a writer and as a citizen of Northern Ireland, his choice to work in the Falls Road and the firebombing of his house by rogue UDA members all make very dramatic reading; and the Loyalist perspective, which he has often written from, is under-represented in Irish theatre. However, the narrative in Love Matters ultimately fails to engage the kind of emotion that the range and breadth of Loyalist experiences in Northern Ireland can undoubtedly yield in a theatrical framework.

Ruth Kennedy is a researcher with The Morning Show on East Coast FM and also works in theatre in education.

Read an Irish Theatre Magazine interview with Gary Mitchell by Jane Coyle here.