His plays, for stage and radio, did not to make for comfortable viewing, given their uncompromising portrayal of violent political and paramilitary feuding and bitter domestic conflict within a closed, intensely private world. They offered a new, unfamiliar and uneasy version of Irishness, not previously witnessed on stage. But producers and audiences across Ireland, in London and far beyond were drawn to the powerful edge of the writing, the twisting, high-tension narratives, the biting black humour and the true-to-life characters.

One by one, in a great flood of productivity, they tumbled out - In a Little World of our Own, The Force of Change, Marching On, Energy, Trust, As the Beast Sleeps, Tearing the Loom, Loyal Women, Remnants of Fear - accompanied by a string of prestigious awards and a writer-in-residence appointment at the National Theatre in London.

For a young man raised in the hotbed of a sprawling estate beset with warring loyalist factions, who left school to take up a lowly job in the civil service, it did not get much better. During the next few years, the world and its wife wanted a piece of him. The phone rang constantly, commissions poured in and he was travelling to meetings here, there and everywhere. From unlikely beginnings, Mitchell’s place in the firmament of Irish writers seemed assured.

He has always been very much his own man and, for all his success, has never quite considered himself a fully paid-up member of the inner circle of the northern arts community. Nor has he been averse to breaking the mould of what might be expected of a writer from his background. His plays were premiered by the Royal Court in London, the Derry Playhouse, DubbelJoint in republican west Belfast and the Abbey Theatre and Mitchell would regularly take parties of family and friends from Rathcoole south of the border to Dublin for opening nights. In turn, he would invite associates from Dublin to Belfast for a guided tour around the place he once memorably described as ‘the hardlands’. They were heady times, indeed.

Then, suddenly and for no reason immediately apparent to him, it all started to fall apart.

“It was as if my career ended about six years ago and certainly not from choice,” he reflects. “At one point I was looking for a job, a real job, where you go to work every day and earn money every week. My wife was sick with a heart condition, which she still has, and we had two little babies, as well as her two older boys. In trying to look after them all, I slowed down and lost confidence. It just became impossible.

“The feeling I get is that, in the years since Loyal Women at the Royal Court (in 2003), I’ve written numerous movies that didn’t get made, lots of stage plays that didn’t get produced. The message was coming to me, loud and clear, that nobody wanted to know about the loyalist community any more. It just wasn’t any longer a fashionable subject nor an area that anyone wanted to explore.

“I tried to offer myself as a writer of other things, but that didn’t work out because I feel I have been pigeonholed as a loyalist voice, a voice for loyalism, whatever. To be honest, I never wanted to be the voice of anything. But I have found myself limited by my own experiences and by what I was allowed to do, what people were prepared to commission. I couldn’t get a chance as someone who just wanted to write good plays, maybe set in my own community but with universal themes. Or even to write plays set in other countries and communities, as other writers are allowed to do. Basically, I was just trying to prove that I was a writer. It was a real Catch 22 situation.”

And there was more - and worse. As his professional career started to unravel, Mitchell became caught up in a situation, which could have come straight out of one of his own plays. Throughout the years that he had been a major force in Irish theatre, he continued to live below the radar in the heart of Rathcoole, among the very people on whom he based his characters. But, eight years ago, when he ventured into more public arena of television, he started to be noticed and the subject matter of his work reached the ears of malevolent forces in the vicinity. The outcome was that he and his wife were burnt out of their home and, in the months that followed, his close-knit wider family had to move away from the estate where they had lived happily for so many years.

Still, one wonders, given his burgeoning international reputation, how did manage to remain unnoticed and embedded in that community for so long?

“Most people in Rathcoole didn’t know what was happening in the theatre or on the radio, so who would know what I was doing?” he says. “The vast majority of people in loyalist communities, who have seen my work, really like it. They think it’s great that stuff is being written that shows our side, shows we’re there. But we have a very dangerous small minority that didn’t like it.

“I went to see people to ask their permission to shoot the film of As the Beast Sleeps in Rathcoole and that’s where the problem started. I was told that cameras weren’t allowed in Rathcoole. It got worse from there, just escalated and never went away. But through it all, I never thought anything would happen, you know?”

Throughout those difficult years, there were, however, glimmers of interest and support from unexpected quarters. Mitchell speaks warmly of Kevin Reynolds at RTE for commissioning a radio play from him every year and of the Abbey Theatre, for putting a play into development, even though, ultimately, it did not come to full production.

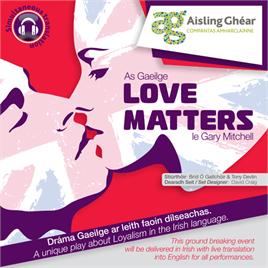

Now, and perhaps most remarkably, Aisling Ghéar Theatre Company, based in An Culturlann, the Irish language arts centre on the Falls Road, has commissioned him to write a new play. Love Matters will be performed in Irish and premiered at An Culturlann (March 1), before transferring to the Lyric Theatre (March 2 and 3) and Project Arts Centre (March 6-10), with the original version delivered to the audience in simultaneous live translation. It is a timely collaboration. The impressively extended An Culturlann was reopened in autumn 2011 by then President Mary McAleese; west Belfast is now an officially designated Gaeltacht quarter; the number of people from both communities starting to learn Irish is growing and more and more children across the city are being educated in Irish.

Mitchell says the notion first came to him many years ago, during a stay at the Tyrone Guthrie Centre at Annaghmakerrig. He found himself helping a young writer, who was struggling with the storyline for a play in Irish and it fleetingly crossed his mind that, some day, it might be interesting to write a play about loyalism, which would be done in Irish.

He explains the storyline of Love Matters as being set in “… peace process Rathcoole. It’s about a guy coming out of prison under the terms of the Good Friday Agreement. He had left behind a wife and baby and told his associates to keep an eye on them. Just days before his release, they realise that they have not looked after them very well and that the boy has grown up to be not a hard man like his father, but a soft, nice young fella, who’s very immature for his years. Meanwhile, the wife is seeing another boy of the same age as her son, a big, aggressive type, who wants to break away from this community. He just happens to be the son of the cop who put her husband inside. So again it’s dealing with universal issues, in a specific place - and that place is Rathcoole.”

He explains the storyline of Love Matters as being set in “… peace process Rathcoole. It’s about a guy coming out of prison under the terms of the Good Friday Agreement. He had left behind a wife and baby and told his associates to keep an eye on them. Just days before his release, they realise that they have not looked after them very well and that the boy has grown up to be not a hard man like his father, but a soft, nice young fella, who’s very immature for his years. Meanwhile, the wife is seeing another boy of the same age as her son, a big, aggressive type, who wants to break away from this community. He just happens to be the son of the cop who put her husband inside. So again it’s dealing with universal issues, in a specific place - and that place is Rathcoole.”

“It’s strange how things work out. I didn’t ever really think I would have a play in Irish and I didn’t think it would be produced on the Falls Road. My life has been the opposite of what I thought it would be and every day becomes more bizarre. I don’t know why, but people around here seem to like me. A few years ago, I was asked to launch the West Belfast Festival and I’ve been invited to various things and always welcomed warmly. Don’t forget, I grew up petrified of this place, thinking that if I was ever walking down this street someone would kill me!”

Over the years, a number of Mitchell’s plays have been translated into other languages. It is a process, which he finds endlessly fascinating and revelatory, never more so than this time around.

“The whole language thing is very interesting to me,” he says. “When I heard one of my plays done in German, the Rathcoole dialect sounded really aggressive and hard; the whole thing sounded more fierce than I had written it, even the sweeter moments. Another play, performed in Hebrew, was completely different. Even the hardest characters sounded passive and afraid.

“The first time I heard this play in Irish, it was like a different world. The translation (by Andrea Higgins) is brilliant. Unbelievable. I just sat there and listened and tried not to think about what I originally wrote and to me it was more like a dance. It’s hard to explain, but it was somehow more joyful or romantic than it sounded in Rathcoole English. I started to wonder, does it have the all anger, does it have the aggression? There is a kind of niceness to it and I like it.

“The first time I heard this play in Irish, it was like a different world. The translation (by Andrea Higgins) is brilliant. Unbelievable. I just sat there and listened and tried not to think about what I originally wrote and to me it was more like a dance. It’s hard to explain, but it was somehow more joyful or romantic than it sounded in Rathcoole English. I started to wonder, does it have the all anger, does it have the aggression? There is a kind of niceness to it and I like it.

“This will be my fortieth professional production. I don’t count plays being done by different theatre companies or even different productions in other countries. I just mean if you count the individual original scripts for television, theatre and radio. Not bad for an idiot from Rathcoole!

“Suddenly I’m busier than I’ve been in the last ten years. I’m writing a follow-up to Energy, catching up with those same characters 30 years on. I’m doing a new radio play and a television pilot for the BBC - I haven’t done anything for them for a very long time. Plus I’m writing a new play for Martin Lynch’s company. It’s like I’ve been offered a second opportunity to have my life back and I just feel so privileged to have been given that chance.”

Jane Coyle is a Belfast-based freelance arts journalist and critic, who also contributes to The Irish Times, The Stage, Culture Northern Ireland and BBC Radio Ulster.