Just what kind of a person was Hildegard von Bingen? Was she, as history records, a devout 12th Century anchoress and mystic, cloistered not only in her abbey, but also in her devotional music compositions and frequent ethereal visions? Or can we make the case for a tortured shut-in, expressing herself in erratic fits and starts; somebody whom the neurologist Oliver Sacks would later diagnose as having one of history’s most famous migraines? Ian Wilson’s Una Santa Oscura, a fragmentary composition for violin embedded in an ambient burble of electronic soundscapes and realised for stage performance by director Tom Creed, suggests that Hildegard was all of the above.

It’s no easy feat to fold a relatively obscure figure from antiquity into a contemporary setting, to parallel her spiritual vesselhood with a portrait of modern isolation. It’s no easier to combine an elliptical violin sonata with a coherent theatrical narrative. (It’s “like an opera without singers,” went one blurb, as though struggling to articulate this mysterious new form of wordless music performance.) The great strength of Una Santa Oscura, rather fittingly, is its faith in performance. This is evident in the absorbing presence of violinist Ioana Petcu-Colan, a lyrical player who pads around Ciarán O’Melia’s bedsit set in her socks, moving gingerly between a partially concealed kitchen at one end and a ruffled duvet at the other, before fetching her instrument – with pronounced scepticism – from the top of a fridge. But it’s also there in the production’s collision of music, stage aesthetic and action, with each party asked to complete the work of the other through a shared belief in harmony.

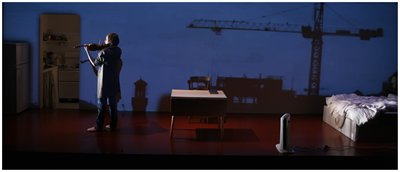

It’s no easy feat to fold a relatively obscure figure from antiquity into a contemporary setting, to parallel her spiritual vesselhood with a portrait of modern isolation. It’s no easier to combine an elliptical violin sonata with a coherent theatrical narrative. (It’s “like an opera without singers,” went one blurb, as though struggling to articulate this mysterious new form of wordless music performance.) The great strength of Una Santa Oscura, rather fittingly, is its faith in performance. This is evident in the absorbing presence of violinist Ioana Petcu-Colan, a lyrical player who pads around Ciarán O’Melia’s bedsit set in her socks, moving gingerly between a partially concealed kitchen at one end and a ruffled duvet at the other, before fetching her instrument – with pronounced scepticism – from the top of a fridge. But it’s also there in the production’s collision of music, stage aesthetic and action, with each party asked to complete the work of the other through a shared belief in harmony.

That it doesn’t entirely cohere, leaving the impression that none of the elements are finished, resembles the inverse of Hildegard’s own problem. Where she struggled to give explanations to her visions, here it’s the other way around. “Everything from what the violin soloist wears… to the sonic and visual props on stage and of course the actual music she performs, relates in some way to Hildegard’s life and context,” the programme informs us, stretching the concept still further with references from ethnomusicology to Sacks’s treatise on migraines. Can these various strands be untangled? More attentive ears might be able trace the inheritance of Hildegard’s gossamer monody, 'Ave Maria O Autrix Vite', in Wilson’s electronically generated recording (in collaboration with John Greenwood and Stephen McCourt), but even experts may puzzle over the significance of, say, Petcu-Colan’s socks.

At under an hour, the performance is carefully encoded, like a religious text that awaits interpretation or an hallucination full of locked meanings. Few will fail to appreciate the parallels that O’Melia’s design draws between anchorage and the urban prison of a dismal bedsit, however, which he somehow lights beautifully with a passage through a single day, adding stylised flickers of spiritual visitation. And as Petcu-Colan produces soft and transporting phrases with her bow that cede randomly to abrasive, unsettling scratches, the expression of both mystic and musician seems engagingly unpredictable – the fruits of uncertain muses.

Accompanied by Jack Phelan’s video design, which daubs the walls with images of urban development (cranes and cityscapes) and misty remembrances (a beach-side walk of distended details, glimpsed while a photo is retrieved from a book), Petcu-Colan’s narrative wavers in and out of our comprehension. It’s as though the makers know that their work functions best at the level of abstraction, yet nobody can bring themselves to bury the evidence of their dramaturgy.

Accompanied by Jack Phelan’s video design, which daubs the walls with images of urban development (cranes and cityscapes) and misty remembrances (a beach-side walk of distended details, glimpsed while a photo is retrieved from a book), Petcu-Colan’s narrative wavers in and out of our comprehension. It’s as though the makers know that their work functions best at the level of abstraction, yet nobody can bring themselves to bury the evidence of their dramaturgy.

When we are allowed to succumb to the experience, without feeling it necessary to chase various clues back to their sources, Wilson’s languorous themes and repeated phrases become more transportative. Over a rippling pond of digital loops, they sound a subtle emulation of the rapture of inspiration and incantation. Whether Phelan’s later projected images of a constellation of pinpricks lights allude to the “extinguished stars” of Hildegard’s visions, or the “migraine aura” so carefully outlined by Oliver Sacks, the loose connection of sound and vision begins to feel like an unresolved equation.

That could be the point. With its disjointed moments and elusive referents, this impressionistic collaboration allows us to construct our own Hildegard and arrive at a wilderness of interpretations. Her experiences, and our responses, can register with the force of anything from divine inspiration to a throbbing headache.