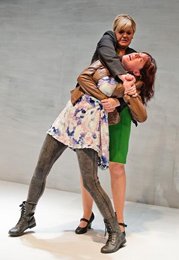

As light rises on the cardboard set of David Ireland’s Everything Between Us, we are bombarded by a sea of expletives. Sandra (Tara Lynne O’Neill) has just taken her seat on the board of the Truth and Reconciliation Committee for Northern Ireland, when her long lost sister Teeni (Claire Lamont) bursts in and attacks the South African chairwoman. Grabbing Teeni around the neck, Sandra drags her to a storage room among the political chambers. As Teeni attempts to escape the chokehold, she screams lurid and racist slurs at the chairwoman beyond: “Apartheid, Apartheid!” “You know you’re in trouble when the South Africans are coming to help you out.”

True North, a series of plays from Northern Ireland’s most promising young writers, refreshes an audience bored with shying away from truth in the theatre. John McCann, Colin Bell and David Ireland collaborate with Tinderbox Theatre Company on an innovative new project of artistic vision and financial practicality. A unique ensemble of players performs in repertory dramas that tackle what it means to live in Northern Ireland today.

Tinderbox is a company passionate about collaboration and dedicated to reviving a rigorous approach to script writing in Northern Irish theatre. In a recent interview, McCann calls the company determined “to assist the writer to explore fully whatever it was that stuck in their craw enough to make him or her write their play in the first place”. They commit to these stories and will go where the writers lead.

These writers aren’t afraid to go too far: they’ll scoff and offend so far as words will allow. Narratives do not steer clear of contentious subject matter; they don’t dodge any political bullets. Boundaries collapse as these characters plough through conventions, putting voice to the politically incorrect and to those disenfranchised by the region’s religious views and politics.

Everything Between Us is characterised by a tone of irreverence. Telling the story of her eleven years away from home, Teeni spares us no gory detail. The account of her alcoholic lurid past reaches a sordid climax as she finds herself with her pants down on a Manchester street, pawing at the crotch of a stranger. Coming back to Belfast, she is horrified by the  compromise her previously Unionist tribe has made for peace. “Daddy wouldn’t know his own daughter,” she says to Sandra, who stands firm in her new vocation. “It’s a lie,” says Teeni of the Truth Commission, “and it has to be stopped”. “Ulster has nothing to gain from it.”

compromise her previously Unionist tribe has made for peace. “Daddy wouldn’t know his own daughter,” she says to Sandra, who stands firm in her new vocation. “It’s a lie,” says Teeni of the Truth Commission, “and it has to be stopped”. “Ulster has nothing to gain from it.”

Teeni’s angry tirades are juxtaposed with moments of purity and forgiveness as the sisters’ relationship begins to mirror the actions taking place in the next room. Brutal and heart wrenching, it’s a personal journey of reconciliation. Humour is dark and controlled, language is vulgar and silence is deafening.

Relying almost entirely upon the power of her talented players, director Kathleen Akerley cleverly navigates the themes of the play. Bigotry, extremism, homophobia, dissidence, hate: issues are tackled head on while the audience listens, safe in the knowledge that these are just words said by an actor. Claire Lamont plays Teeni as moderately reformed but still deeply unhinged, using her body to full affect, her flailing limbs a thermometer for shifts in the action’s emotional levels. Lighting is unobtrusive, illuminating the stark daylight reality of Teeni’s intolerance.

This production is deeply affecting, leading its audience down a difficult path. David Ireland’s writing is an assault on the state of denial, displaying the shame and revulsion inherent in any mechanism for dealing with the past. “It horrifies me to be a human being,” says Sandra.

John McCann’s The Cleanroom takes us on a similar journey of recovery. Molly (O’Neill) volunteers to transfer to the pharmaceutical cleanroom to help Karen (Laura Hughes) and her team survive budget cuts. It transpires, however, that Molly has a personal motive. Magee (Paul Mallon), the room’s resident bigot, previously caused a serious car accident in which Molly’s friend was fatally wounded and Molly injured. She’s here to look him in the eyes, to finally conquer her anger.

The room is a clinical space with clear plastic and wiped surfaces. Cold lights bounce off white walls and sparse furnishings, the sterile countertops free of germs and bacteria and employees wear plastic boiler suits. It cannot escape contamination, however, by political and personal attitudes. McCann asserts that the seemingly high-tech veneer conceals a low-skilled and low-paid reality. Personal opinions seep into the controlled environment, unhinging the balance of the space.

The room is a clinical space with clear plastic and wiped surfaces. Cold lights bounce off white walls and sparse furnishings, the sterile countertops free of germs and bacteria and employees wear plastic boiler suits. It cannot escape contamination, however, by political and personal attitudes. McCann asserts that the seemingly high-tech veneer conceals a low-skilled and low-paid reality. Personal opinions seep into the controlled environment, unhinging the balance of the space.

Other narrative strands intersect the dominant storyline. Karen is recently widowed and her late husband’s cronies sit on her house day and night. They’re making it difficult for her to continue her secret relationship with co-worker Saul (Ivan Little). Tension manifests itself in glances between the pair, picked up by the other workers.

The question that hovers over the action: what happens when they tell us today is our last day? Faced with financial upheaval, the bosses lay off hoards of employees each day. Increased productivity may delay the room’s fate indefinitely but they can’t avoid unemployment forever. The administration remains tight-lipped and the group becomes increasingly anxious as minutes tick by. They attempt to assign blame, accusing the suits of negligent greed and scapegoating Polish immigrants who’ll do the job for half the wage.

Political prejudices form the backdrop of the piece, set in Craigavon. “He wants to know which foot she kicks with,” says one employee of Magee, who can’t say hello to anyone without sounding like a bigot. McCann was interested in hearing colloquial voices and seeing local issues explored in this clinical setting. ‘If I had written this play ten years ago’, he says, ‘it would be very different to how it is today. The play is about the intervening decade and how events outside the room have pushed characters to where they are now in this particular part of Northern Ireland, a place where a ‘peace dividend’ is something that happened somewhere else.’

A fine balance is struck between high-tension and moments of explosive drama but the narrative arc of the play is left largely undefined. Due diligence has not been done to ensure that the audience can find its footing in the narrative. Karen and Saul’s relationship remains insufficiently explored and falls into obscurity once the primary action begins. Dialogue is occasionally stunted and unnatural but rescued by a fine ensemble depicting a group wracked with frailty and doubt over their future.

Playwright Colin Bell has been under pressure to defend his play God’s Country from accusations that it is a direct attack on former MP Iris Robinson. Bell insists that the third instalment of True North deals predominantly with the transformation of the DUP since ‘Irisgate’- a political scandal in which Robinson (notorious for publically calling homosexuality an abomination) was revealed to be having an affair with a man 41 years her junior and procuring loans to help him set up a business.

Playwright Colin Bell has been under pressure to defend his play God’s Country from accusations that it is a direct attack on former MP Iris Robinson. Bell insists that the third instalment of True North deals predominantly with the transformation of the DUP since ‘Irisgate’- a political scandal in which Robinson (notorious for publically calling homosexuality an abomination) was revealed to be having an affair with a man 41 years her junior and procuring loans to help him set up a business.

The action opens during a nightmare. Jamie (Mallon) lies in a small rowing boat, his semi-naked body just visible in the speckled light. He is calm for a moment before his frame begins to contort. There is a story playing out in his mind. “I’m not a weakling” he whispers defiantly, backing up against the wall, rocking back and forward on his tiptoes. His eyes bulge from their sockets. He is in agony.

His mother, fictional MLA Patricia Williamson (Hughes), prepares to address the murder of Declan Campbell, a young gay man in her constituency. Her party advisor (Lamont) strongly suggests communicating a sense of empathy and condolence, reassuring moderate voters that the party has learned from the Robinson debacle. Williamson, however, stays true to her ideals. She condemns homosexuality, the moral subsidence of a nation, and the betrayal of godly ideals.

When Jamie returns home from London with his partner Jonathan (Patrick Buchanan), Patricia must face up to the tormented history of her own family. The dialogue reeks of generic religious platitudes and homophobic slurs, exposing the bigotry inherent in the structure and politics of Northern Ireland. Even in Williamson’s husband’s fuddled state after a recent stroke, he manages to denounce his son’s relationship. Bell confronts the reality of life for the region’s gay population.

Mallon gives a measured and vulnerable performance as a man determined to reconcile with hostile parents. A tender kiss between Jamie and Jonathan marks a pause. An action rarely seen on the streets of Belfast, it strikes a chord with the audience. We are transfixed.

Colin Bell paints a strikingly accurate image of how religious views and political choices are irreversibly intertwined in Northern Ireland’s governmental system. He depicts elements of extremism and bigotry in every facet of administration. The voices of Bell, Ireland and McCann, cut close to the bone. This is not a generation of writers immune to the influence of the Troubles: they deal with the conflict as the legacy of the country we live in now and the dark past that we’re slowly beginning to escape.

Kathy Clarke is an arts journalist based in Belfast.