Can you have a performance about a solitary, disconnected figure, who has strayed far from home, without making a departure? “I’m not from here,” begins Conor Lovett’s nameless speaker, his eyes darting to the still-open door of the auditorium. “I never will be, I guess.” Why, then, does he seem so securely at home?

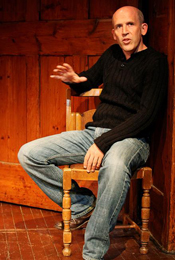

With only teasing, slippery references to place, if Will Eno’s new play Title and Deed is set anywhere it’s the discomfort zone. It isn’t the first new play that Gare St Lazare Players Ireland have staged, but since 1996 the company’s repertoire has prioritised Lovett as a Beckettian monologist, delivering prose texts as unembellished solo performances. It’s doubtless a tricky negotiation, for both artistic and legal reasons, but Gare St Lazare Players’ success has made the company synonymous with the deracinated souls of Beckett’s work. Lovett and director Judy Hegarty Lovett have constructed faithful, entirely unadorned renderings, in which Lovett’s compelling persona conveys something both approachably human and unbridgeably distant. Hesitant and sympathetic, Lovett’s is a voice that ebbs and flows keeping the words intact, but making them sound as though they might elude him at any moment.

Eno wrote Title and Deed specifically for the company, inspired by a New York performance of Beckett’s The End at the beginning of this year. In that performance, Lovett played another nameless figure who returns to a city both familiar and alien. It’s not clear what Eno has to add to that uprooted character, other than a contemporary idiom, and it’s not clear what Gare St Lazare Players take from Eno other than more material to suit that Beckettian style. What few threads there are to hold the monologue together – musings on displacement, estrangement and fear – begin to fray quickly against the realisation that we are going nowhere.

.jpg.aspx) Eno’s monologues are clearly indebted to Beckett, but where the narrators of Beckett’s prose are as cold and absurd as a meaningless universe – think of Malloy sucking stones or knocking on his mother’s skull – Eno’s characters come off as existential wiseacres. “I’m like whatever,” says the off-handed speaker of Thom Pain (based on nothing), before adding, with grave intent, “I really am like whatever.” The character of Title and Deed feels like a compromise, a mildly bewildered but generally good-natured smartass. He has arrived from his small, unspecified country, described with a see-saw of universalities and idiosyncrasies, and ingratiates himself with something between absurdism and observational humour.

Eno’s monologues are clearly indebted to Beckett, but where the narrators of Beckett’s prose are as cold and absurd as a meaningless universe – think of Malloy sucking stones or knocking on his mother’s skull – Eno’s characters come off as existential wiseacres. “I’m like whatever,” says the off-handed speaker of Thom Pain (based on nothing), before adding, with grave intent, “I really am like whatever.” The character of Title and Deed feels like a compromise, a mildly bewildered but generally good-natured smartass. He has arrived from his small, unspecified country, described with a see-saw of universalities and idiosyncrasies, and ingratiates himself with something between absurdism and observational humour.

Nervous before the airport security (“I began to tell the truth and feel like I was lying.”) he is asked, business or pleasure? “I’m here to save us all.” And who is us? “‘Exactly’, said I with a wink.”

Who is us, is a good question, but it troubles Eno even less than who his character is. A traveller seeking a connection, Lovett speaks to the audience directly, but as a mass, his shy smiles and rhetorical questions (“Maybe you have that here?”) feel like a feint and the audience abandon trying to tease out his providence, and eventually his significance.

We like to believe that the legacy of the theatre of the absurd is that of path-breaking performance, a movement that is critically alive to the immediacy of the audience, the lie of artifice, and the terror of existence. It’s closer to the truth to say its legacy is college humour; a hyper-aware, know-it-all comedy fluent in self-defeating irony. “Is this the part where I say, we’re not so different you and I?” asks Lovett. Eno has the distance of the wit, hovering above words to watch them slip or fail. This character has “one foot in the grave and the other in my mouth”, considers love a “many splintered thing” and is bemused by people who try to make him feel at home “despite never being at my home”. And though Lovett makes the spiel amusing, forcibly recalling the faux-naïve absurdity of Kevin McAleer, the question is never about where this riff is going, but just how long Eno and Lovett can sustain it. There are nods to mortality – the threat of thunder, his clicking jaw and dry throat – and allusions to the impossibility of home, but the play would rather tail off than become embarrassed by significance. “I’m shooting for the essential here,” says Lovett, but he is really like whatever.

We like to believe that the legacy of the theatre of the absurd is that of path-breaking performance, a movement that is critically alive to the immediacy of the audience, the lie of artifice, and the terror of existence. It’s closer to the truth to say its legacy is college humour; a hyper-aware, know-it-all comedy fluent in self-defeating irony. “Is this the part where I say, we’re not so different you and I?” asks Lovett. Eno has the distance of the wit, hovering above words to watch them slip or fail. This character has “one foot in the grave and the other in my mouth”, considers love a “many splintered thing” and is bemused by people who try to make him feel at home “despite never being at my home”. And though Lovett makes the spiel amusing, forcibly recalling the faux-naïve absurdity of Kevin McAleer, the question is never about where this riff is going, but just how long Eno and Lovett can sustain it. There are nods to mortality – the threat of thunder, his clicking jaw and dry throat – and allusions to the impossibility of home, but the play would rather tail off than become embarrassed by significance. “I’m shooting for the essential here,” says Lovett, but he is really like whatever.

The sad consequence is that the production threatens to become an exercise in self-parody, with both writer and company too easily at home in the discomfort zone. Contentedly thin on substance, the play draws more attention to Lovett’s technique, his contrapuntal rhythm and uncertain mannerisms, thickening the suspicion that the style could be put as easily to the service of Beckett, Herman Melville or the phone book without much variation. Ultimately Title and Deed feels like less like a detour from Beckett than a spin-off, as though the company’s international success could become an artistic agoraphobia. Home, like a secure performance style or a fixed identity, may indeed be hard to find; but the impression of this production is that it can also be very difficult to leave.

Peter Crawley