The furore around the first production of The Sanctuary Lamp at the Abbey Theatre in 1975 tells us more about the tyrannical and despotic hold the Catholic Church had over the minds and hearts of the nation than it does really about Tom Murphy’s brilliant drama itself. Granted, there are some glorious tirades against, jibes at and critiques of the Catholic Church and its cruel dogma – and Murphy was unafraid to voice these critical incisions at a time when it wasn’t popular to do so. However, a truly big play with large themes, there’s so much else going on. At the very least, The Sanctuary Lamp looks at the nature of belief itself – or faith and non-faith – subjects which transcend any one religion or place or time. This latest production, directed by the playwright himself, still contains all the Rabelaisian force one would expect from someone who had suffered daily at the hands of the Catholic Church’s dictatorship, but Murphy’s direction also clearly wants to allow the myriad layers and subtleties of all the themes air to breathe as they mingle with his typically earthy Irish paganistic amoralities of the flesh. Thus, there is a touching gentleness to this production as if to emphasise its humanism and make the point that it’s not merely all-out attack on the institution of Catholicism.

Ostensibly, The Sanctuary Lamp tracks the destitute and desecrated lives of three individuals with generational gaps between their ages as they congregate in a barren, dark and cold church somewhere in London. Harry (Robert O’Mahoney) is a one-time circus strongman, devastated mostly by the death of his young daughter; Maudie (Kate Brennan), though still not more than a child herself, probably mid-teens, has herself lost a child; and Francisco (Declan Conlon) is a juggler (of not only balls but ideas too), a friend who ended up stealing Harry’s wife, Olga.

Harry, Maudie and Francisco are all very real, imperfect human beings but they are also a Holy Family of Father, Holy Ghost and Jesus, respectively, but Jesus as rebel not conservative soporific. Dressed in a white, holy communion-style dress Kate Brennan plays Maudie in an ethereal, spiritual and child-like innocent, holy dove way. Robert O’Mahoney’s sonorous delivery is enhanced by the addition of church echo to his words; this lends an epic, divine air to the figure he cuts. Dishevelledly dressed in a casual waistcoat and with long unkempt hair, and wielding most of the time a bottle of wine and a cigarette, Declan Conlon’s Francisco is all bohemian and wounded flesh. In other words, he is Christ’s humanism, and flawed and struggling humanity in general, as he fires his barbs with drunken flourish and resignation at the hypocrisy of the world around him and Catholicism, in particular. They are also an axis of Judeo-Christianity: Harry is Jewish, Maudie is Prostestant and Francisco Catholic.

Harry, Maudie and Francisco are all very real, imperfect human beings but they are also a Holy Family of Father, Holy Ghost and Jesus, respectively, but Jesus as rebel not conservative soporific. Dressed in a white, holy communion-style dress Kate Brennan plays Maudie in an ethereal, spiritual and child-like innocent, holy dove way. Robert O’Mahoney’s sonorous delivery is enhanced by the addition of church echo to his words; this lends an epic, divine air to the figure he cuts. Dishevelledly dressed in a casual waistcoat and with long unkempt hair, and wielding most of the time a bottle of wine and a cigarette, Declan Conlon’s Francisco is all bohemian and wounded flesh. In other words, he is Christ’s humanism, and flawed and struggling humanity in general, as he fires his barbs with drunken flourish and resignation at the hypocrisy of the world around him and Catholicism, in particular. They are also an axis of Judeo-Christianity: Harry is Jewish, Maudie is Prostestant and Francisco Catholic.

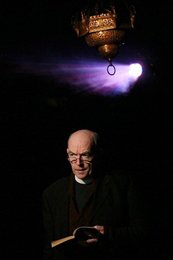

Into this melee, and marginal to it, is the Monsignor (Bosco Hogan) of the church where the action takes place. The Monsignor, too, appears forlorn and lost yet he is almost beyond the existential crisis that Murphy lays bare before us - not because he’s superior to it but because he represents a movement towards Buddhism: he’s reading Herman Hesse, can’t put it down and spends every free minute of his day glued to the text. (In the religious context of the play we can be sure it’s Hesse’s meditation on Buddhism, Siddhartha that has so captivated the Monsignor.) Significantly, and no doubt at Murphy’s direction, Hogan plays the Monsignor as a sympathetic, egoless, gentle, isolated, apologetic and disillusioned figure. Under different direction, he could just as easily have been haughty, detached and disinterested.

The set is striking. A confession box takes centre stage, out of which Maudie emerges. (We hear a lot of confessions from the characters, but to each other, mostly.) It’s dark. Surreally huge columns extend forever upwards dwarfing the human beings. There’s a pulpit stage right. As if to emphasise all the smoke and mirrors of Catholicism and to simulate the burning of incense, mist or smoke swamps the set in the beginning. A sanctuary lamp, of course, hangs from the ceiling too. Its red light, representation of God and Spirit, shimmers throughout. As the Monsignor reminds Harry, it’s really just a candle that needs to be replaced once every twenty-four hours. So much for all the hocus-pocus about soul and spirit. Yet Harry still addresses it as if God was really contained within it, watching and listening to every sad appeal and invocation.

The set is striking. A confession box takes centre stage, out of which Maudie emerges. (We hear a lot of confessions from the characters, but to each other, mostly.) It’s dark. Surreally huge columns extend forever upwards dwarfing the human beings. There’s a pulpit stage right. As if to emphasise all the smoke and mirrors of Catholicism and to simulate the burning of incense, mist or smoke swamps the set in the beginning. A sanctuary lamp, of course, hangs from the ceiling too. Its red light, representation of God and Spirit, shimmers throughout. As the Monsignor reminds Harry, it’s really just a candle that needs to be replaced once every twenty-four hours. So much for all the hocus-pocus about soul and spirit. Yet Harry still addresses it as if God was really contained within it, watching and listening to every sad appeal and invocation.

Sound designers and composers Ivan Birthistle do a great job by adding a churchy, ecclesiastical echo at times. This reverberation adds to the resonance of what is said even if there are moments when its larger-than-life effect detracts from the humanity of the particular human plight of Harry, Maudie and Francisco. While all the performances are near faultless, Declan Conlon is especially excellent as Francisco, who has escaped the manacles and indoctrination of religion and doesn’t share Maudie and Harry’s yearning for divine answers or intervention, yet he carries the scars of his philosophical battles heavily. Conlon’s fire and brimstone distillation doesn’t shirk from showing us Francisco’s flaws but it also allows us to see, albeit through resigned indignation, Francisco’s deep humanity and sense of justice.

Most of all, thanks to Tom Murphy’s generous direction which allows the actors the space and confidence to tease out the nuances of their roles, this production enables us to see what a profound and complex play The Sanctuary Lamp is. Far from being merely anti-religious, this production suggests most poignantly that the only sanctuary we can hope for in this life really is that which comes in the form of the troubled solace we get from the company of our fellow human beings and not in illusory, perpetually burning candles of false hope. Nevertheless, even as Murphy’s choreography allows the performances of his characters a musical, balletic and tragic grace, for all the crushed dignity humans share, there persists a yearning for the non-human.

Patrick Brennan was chief theatre critic and main arts writer with the Irish Examiner from 1990-2004. He is currently writing a book on the theatre of Tom Murphy.