This new production from Decadent Theatre is described in the programme as the company’s fourth “world-premiere”. That claim might seem extravagant for a group that isn’t well known beyond Galway, but it captures well the ambition – and, more importantly, the achievements – of the company, which has been producing some excellent work recently. In 2008, for instance, they gave us an intriguing revival of Martin McDonagh’s The Lonesome West, while last year they premiered Here We Are Again Still, which is probably Christian O’Reilly’s best play to date. So Decadent have quickly become a company that deserve to be better known throughout Ireland – and a company that you can’t help wishing the best for.

For that reason, this production of The Quare Land produces a mixed response. It asserts comprehensively Decadent’s ability to stage a play that matches (and sometimes exceeds) the work of many of our regularly-funded companies. Yet it doesn’t quite reach the standards that the group has set to date.

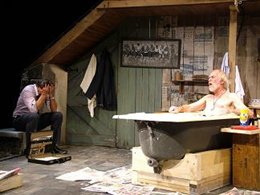

What is immediately impressive here is the company’s achievement in presenting the first play of a genuinely interesting new writer. John McManus has given us a two-hander about greed – in which a smarmy but stressed-out property developer (O’Sullivan) attempts to buy a field from a decrepit farmer called Hugh Pugh (Keogh). As the play opens, Pugh is taking his first bath in several years – so the confrontation between the two men is carried out exclusively in Pugh’s bathroom.

What is immediately impressive here is the company’s achievement in presenting the first play of a genuinely interesting new writer. John McManus has given us a two-hander about greed – in which a smarmy but stressed-out property developer (O’Sullivan) attempts to buy a field from a decrepit farmer called Hugh Pugh (Keogh). As the play opens, Pugh is taking his first bath in several years – so the confrontation between the two men is carried out exclusively in Pugh’s bathroom.

The setting might be strange, but much of the play will seem familiar. With its dramatisation of a land-grab, its dependence on lost letters to move the plot forward, and its anarchic humour, The Quare Land will readily remind viewers of John B. Keane. And with its rhythmic use of dialogue, its crudity, its joy in pushing against taboos, and the darkness of its conclusion, it will also call to mind the Irish plays of Martin McDonagh (as will McManus’s claim in interviews that he hadn’t much interest in theatre before he started writing).

Yet there is an originality of insight here too, especially in McManus’s exploration of Irish attitudes to land. In the play, Pugh discovers that for many years, he’s been the owner of a field in Leitrim. Rather than being delighted with this news, he instead wants to know how he can use that windfall to acquire even more wealth – much to the property developer’s frustration. McManus’s point is that the sudden acquisition of money doesn’t produce prosperity – it instead encourages greed.

What makes the play more than just a satire on the Celtic Tiger years is that McManus reminds us repeatedly of how, only a few decades ago, Irish men were also obsessed with property – not because they bought and sold it, but because they built it for other people, in London and New York and elsewhere. He therefore aims to historicise our attitudes to land, showing that the greed evident in recent years needs to be understood as a reaction to the poverty that dominated Irish life prior to the 1960s. This, then, is an extremely funny play but with a serious point to make – one that applies as much to the audience as it does to the characters on stage: far from being an anomaly, the Celtic Tiger period is just one more example of our warped attitude to property in this country.

The major disappointment for me was that the play’s depth – and its darkness – were generally lost on the audience. There are a few possible reasons for this problem.

One is that, on the night I attended the play, the audience was unusually chatty. When, for instance, one of the characters on stage said that older women are more desirable, someone in the back row got one of the biggest laughs of the night when she yelled “hear, hear” in response. Similarly, some members of the audience were audibly predicting the punch-lines of the jokes, though to be fair their laughter seemed both heartier and richer when they were proven right. And sitting close to me was a couple who were narrating everything that happened on-stage – so that, for instance, when Keogh pulls a bottle of Guinness from a toilet cistern, the man turned to the woman and said “Oh Jesus, he’s after taking a bottle of Guinness out of the toilet”.

.jpg.aspx%3Fwidth=260&height=195) It would be wrong to make assumptions about the play based on the reactions of some people in the audience during one night in the play’s run – but I think it’s fair to say that Des Keogh’s performance as the farmer was so charismatic and so funny that it invited the kind of response I’ve described above: the audience’s admiration for his comedic skill was so great that it made it difficult for us to appreciate any other aspects of the play.

It would be wrong to make assumptions about the play based on the reactions of some people in the audience during one night in the play’s run – but I think it’s fair to say that Des Keogh’s performance as the farmer was so charismatic and so funny that it invited the kind of response I’ve described above: the audience’s admiration for his comedic skill was so great that it made it difficult for us to appreciate any other aspects of the play.

So I’d have liked to see McManus trying to slow the action down as he moved towards a conclusion – so that the audience could take the time to think about what they were seeing. And perhaps O’Sullivan’s character could have been better developed. And finally, as director, Rod Goodall could have intervened to bring better balance to the play overall. He does many things very well, especially in his use of visual humour and his pacing of the action – and he presents a play that has its audience laughing heartily for well over an hour. But the script is good enough – and the actors talented enough – to have given us something much more than that.

So the overall impression created here is that McManus is a writer who deserves to be watched closely. And it’s impossible not to admire Keogh’s skills as a performer. But, although this play is likely to be hugely popular wherever it travels to, I can’t help thinking that Decadent really are better than this.

Patrick Lonergan teaches at NUI Galway.