The Ones Who Kill Shooting Stars is set in the midst of The Emergency in Ireland during the Second World War. Since Drogheda-based Upstate Theatre’s mission statement promises to draw upon the culture and history of the town and its county, this absurdist and strangely romantic drama particularly focuses on an area of the coast of County Louth – Clogherhead Beach to be precise. As the programme note by archaeologist Dr Geraldine Stout informs, Ireland’s coast was littered with lookouts and watchmen on guard in case of invasion, though whether from the English or the Germans no one seems to have been quite so sure. This, then, is the backdrop to Conall Quinn’s wildly surreal and humorous play, the theatrical precursors of which are Edward Bond, Samuel Beckett and J.M. Synge as much as Flann O’Brien (in a different genre, of course).

Henry (Conan Sweeny), pure Christy Mahon from Synge’s Playboy but more demented by far and more modern, is the slightly deranged, totally alcoholic romantic loner whose task it is to keep lookout and track the comings and goings on the coastline. His logbook, though, is more likely to contain notes about visitations from his dead father than mundane facts about nothing happening, in between his trigger-happy tendency to fire his flare gun into the night sky for the hell of it or to "kill the shooting stars". Henry is prone to peasant-like but highly poetic ejaculations, a la Synge’s Playboy. Keeping him company on the beach is Edward (Karl Quinn), a hilarious embodiment of the Irish middle-classes of the time – Edward is all repressed pretension and mock grandiloquence, fervently nationalistic and high-minded except when it comes to raiding the pockets of the dead pilots washed up onto the coastline.

Henry (Conan Sweeny), pure Christy Mahon from Synge’s Playboy but more demented by far and more modern, is the slightly deranged, totally alcoholic romantic loner whose task it is to keep lookout and track the comings and goings on the coastline. His logbook, though, is more likely to contain notes about visitations from his dead father than mundane facts about nothing happening, in between his trigger-happy tendency to fire his flare gun into the night sky for the hell of it or to "kill the shooting stars". Henry is prone to peasant-like but highly poetic ejaculations, a la Synge’s Playboy. Keeping him company on the beach is Edward (Karl Quinn), a hilarious embodiment of the Irish middle-classes of the time – Edward is all repressed pretension and mock grandiloquence, fervently nationalistic and high-minded except when it comes to raiding the pockets of the dead pilots washed up onto the coastline.

Anything goes in this theatrical space. Thus it is that the freedom-yearning, romantically-lustful Alice (Aine Ní Laoghaire) - a dreamy girl who runs away from home regularly even though there’s no one in her home to hold her down anymore - falls in love with one of the dead pilots, an American by the name of Eugene F. Dumas (John Currivan). Managing to just about skirt the taboo subject of necrophilia, for most of the rest of The Ones Who Kill Shooting Stars we are treated to Alice’s romantic and not-so-romantic intertwinings with, first of all, a totally lifeless Eugene F. Dumas but then, as both Henry and Edward succumb to her resurrectionist spell, Eugene appears as alive as you or me. Thus, in the beginning Alice talks to and kisses the dead Eugene; then, in the second act, Eugene (though still dead), is totally alive. Furthermore, he’s joined by more dead pilots who come alive. Alice’s desire for a man is so bad, of course, that even a dead one is better than none at all.

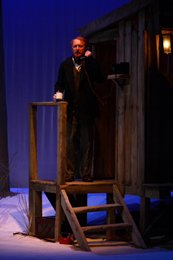

Although simple and minimalist, Kieran McNulty’s set design is strikingly effective and appropriately surreal at the same time. A small raised wooden cabin stands stage right with the important addition of a telephone of the era perched outside. The whiteness of the sand and the rectangular shape of the dune remind us that this is not a realist mise-en-scène. A line of off-kilter telegraph poles too close together stretching diagonally across the dune introduce the parochial element in the play, a fact reinforced by Henry and Alice’s great Drogheda accents. (In keeping with his comical pretentiousness, Edward battles to overcome his accent with a flawed posher tone.) The deliberately incongruent almost tropical lighting provides a sense that this really could be anywhere, any time too - in contradistinction to it being at the same moment very much a particular place in time. Sarah Jane Shiels’ lighting is impressive throughout as it creates night time, moonlit darkness, scorching day, half light and a kind of twilight zone limbo through which shadowy ghosts pass and mingle with our ‘heroes’, Henry, Alice and Edward.

Although simple and minimalist, Kieran McNulty’s set design is strikingly effective and appropriately surreal at the same time. A small raised wooden cabin stands stage right with the important addition of a telephone of the era perched outside. The whiteness of the sand and the rectangular shape of the dune remind us that this is not a realist mise-en-scène. A line of off-kilter telegraph poles too close together stretching diagonally across the dune introduce the parochial element in the play, a fact reinforced by Henry and Alice’s great Drogheda accents. (In keeping with his comical pretentiousness, Edward battles to overcome his accent with a flawed posher tone.) The deliberately incongruent almost tropical lighting provides a sense that this really could be anywhere, any time too - in contradistinction to it being at the same moment very much a particular place in time. Sarah Jane Shiels’ lighting is impressive throughout as it creates night time, moonlit darkness, scorching day, half light and a kind of twilight zone limbo through which shadowy ghosts pass and mingle with our ‘heroes’, Henry, Alice and Edward.

Trevor Knight’s sound design delightfully mixes tunes of the period such as Irving Berlin’s 'I Threw A Kiss in the Ocean' and '(I’ve got a gal in) Kalamazoo' with searing realism like when a plane flying low is simulated so well you almost duck, so that for a moment you’re shaken by the deafening closeness of the aural attack. Then by contrast we’re back into the gentle sounds of the lapping waves at full tide or more of those nostalgic tunes so full of the zeitgeist of the 1940s.

The performances are superb from all the cast, even from Duncan Lacroix who plays a series of dead bodies and gives a whole new meaning to the term ‘corpsing’ on stage. (Ahem.) Conall Quinn’s writing and dialogues are at times breathtakingly poetic and yet hilarious, too. In the midst of all the surrealism and playfulness, subjects like loneliness, frustrated desire, the social repression and hypocrisy of De Valera’s Free State, and hope and hopelessness are touched upon.

However, there’s also an eerie pre-current-recession lightness to The Ones Who Kill Shooting Stars which jars slightly with the nowadays mood and makes it come across as a little bit trivial at times. It is magnificently theatrical, nevertheless, in that gloriously absurdist tradition which flaunts irreverence at all that should be upbraided – even if, at the end of the day, it hinges a little too much on the over-used scenario of girl-meets-boy, their doomed love story and a somewhat clichéd romanticism.

Patrick Brennan was chief theatre critic and main arts writer with The Irish Examiner from 1990 to 2004. He is currently writing a book on the theatre of Tom Murphy.