The St Patrick’s Bacchanalia was in full swing on the streets when the Beckett fans took shelter in the Cork Opera House where Gare St Lazare Players were staging a number of Beckett prose works, alongside Gaitkrash’s wonderful production of Play. Meanwhile, over at the Granary, the UCC Drama and Theatre Studies Department was presenting American actor Michael Murphy in Krapp’s Last Tape, and a group of MA students were performing their own multi-media devised response to moments and characters from Beckett and his contemporaries. So Conor Lovett’s bravura performance of the selection (by himself and director Judy Hegarty Lovett) from the Beckett trilogy, Molloy, Malone Dies and The Unnamable turned out to be the centrepiece of a mini-festival of Beckett works. These pieces have been touring the world for several years but this was a rare opportunity to see them together.

The Beckett Trilogy consists of three works featuring lone narrators charting process of gradual disintegration. Molloy was the first part of the evening and its surreal narrative and mordant humour completely engaged the audience. It began with Molloy’s system of communicating with his deaf, blind mother by knocking on her head (“one knock meant yes, two no, three I don’t know, four money, five goodbye”) and such is Lovett’s precision, directness and charm that even the most gruesome details become mordantly comic. The innate tragicomic richness of the material drew from Lovett a series of wonderful moments and vignettes. Hegarty Lovett and Lovett chose to select mainly from the first part of the novel (focused on Molloy) but, oddly, omitted the very familiar “sucking stones” section. However, Lovett’s bravura deadpan presentation of the lady with the dead dog more than compensated for this. Molloy was by far the most successful sequence in the performance.

Malone Dies famously begins with the line “I shall soon be quite dead, in spite of all” and proceeds with a man recording the process of his own death, distracting himself with narratives from the world of his room, bed, notebook and pencil. We quickly realise we are in a world of mirrors, of shifting narrative layers where the narrator interrupts and changes his own narratives whimsically, where characters are invented, changed, dismissed or murdered on a momentary impulse. Never has Beckett seemed closer to Flann O’Brien. Several hilarious murders later, we arrive at the final disintegration of Malone. And that is (more or less) where the final piece begins.

The Unnamable - “Where now? Who now? When now?” - plunges us into a kind of spiralling, existential vertigo. It is the most difficult text of the three, and at times the audience struggled to stay in touch with the churning questions and multiplying uncertainties that plagued the protagonist. Despite that, it too had its moments of theatrical brilliance, not least the very final movement - “I don’t know, I’ll never know, in the silence you don’t know, you must go on, I can’t go on, I’ll go on” - which saw the performer walk back into his own shrinking shadow and vanish.

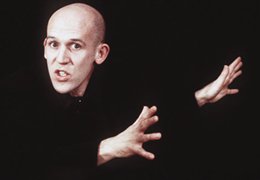

It is perhaps the best tribute to director/designer Judy Hegarty Lovett and lighting designer Sara Jane Shiels that the focus of this three-hour production stayed entirely on the performer. This is appropriate, for Conor Lovett has emerged as a world-class interpreter and performer of Beckett’s prose. His work is a masterclass, demonstrating extraordinary magnetism and disarming directness, allied to a splendid physical precision, both working in the service of his and his director’s clear grasp of Beckett’s text. At times his performance is touched with pathos: he seems to have arrived on stage by accident and to be looking for a way to escape without offending the audience. There are elements of clown in the stance and costume. And yet, we also recognise the precision and physical presence of a dancer. Every twitch of his hand or shift of his booted feet articulates some baffling internal struggle and carries his audience along on whatever journey he wishes to take. Even his uncertainties radiate authority and purpose. When, as Molloy, he lapses into silence and then looks at us and says “I don’t know how I got here”, the line hovers between nervous breakdown and disarming admission. Watching the production, however, I was haunted by the thought of wanting to liberate Lovett for a while from Beckett – perhaps into Flann O’Brien, or even James Stephens – to explore other dimensions of that particularly Irish territory of laughter on the edge of darkness.

It is perhaps the best tribute to director/designer Judy Hegarty Lovett and lighting designer Sara Jane Shiels that the focus of this three-hour production stayed entirely on the performer. This is appropriate, for Conor Lovett has emerged as a world-class interpreter and performer of Beckett’s prose. His work is a masterclass, demonstrating extraordinary magnetism and disarming directness, allied to a splendid physical precision, both working in the service of his and his director’s clear grasp of Beckett’s text. At times his performance is touched with pathos: he seems to have arrived on stage by accident and to be looking for a way to escape without offending the audience. There are elements of clown in the stance and costume. And yet, we also recognise the precision and physical presence of a dancer. Every twitch of his hand or shift of his booted feet articulates some baffling internal struggle and carries his audience along on whatever journey he wishes to take. Even his uncertainties radiate authority and purpose. When, as Molloy, he lapses into silence and then looks at us and says “I don’t know how I got here”, the line hovers between nervous breakdown and disarming admission. Watching the production, however, I was haunted by the thought of wanting to liberate Lovett for a while from Beckett – perhaps into Flann O’Brien, or even James Stephens – to explore other dimensions of that particularly Irish territory of laughter on the edge of darkness.

Ger FitzGibbon is the former head of Drama & Theatre Studies at UCC.