Just getting to the apartment where Request Programme takes place involves navigating numerous lifts, stairs, and a showy Japanese garden. We enter the modern two-bed residence at different stages, one by one. Before the central figure in this performance (Walsh) arrives home from work, we have up to 15 minutes to inspect the space, and attempt to build a picture of her personal life. Designed by Paul Keogan, aside from rows of books, a few childhood photographs, cosmetics and bills, it’s a fairly impersonal expanse, most likely still furnished in the style in which it was bought. A large television screen takes over the hearth, and the apartment obnoxiously comes to a point like the glass-fronted bow of a ship, providing panoramic views of Cork city.

Directed by Pat Kiernan for Corcadorca, Franz Xaver Kroetz’s 1973 wordless, one character play is set in The Elysian residential tower block, which crassly carries the slogan more fitting of a clothes store or glossy magazine: ‘A Very Stylish Affair.’ Launched in 2009, 80% of apartments in the 17 storey building remain unsold, earning it the reputation of being the city’s prevailing symbol of Celtic Tiger excess. Dwelling at the top of this building, we can infer that Ms Evelyn Roche – who, according to her badge, works in accounts at Aviva – at least once benefitted from the boom herself. Whatever her current fortunes, she lives in a largely empty building, closer to the clouds than other people.

Eileen Walsh is one of those actors who is always interesting to watch, even when silent and still. In this hour-long performance, she doesn’t speak a word, yet manages to draw our attention back, even when it wanders aroud the space. Returning from the office, she brusquely sets about swatting a fly, wiping the sill, and cleaning the dishes, even before she removes her stilettos and fitted suit. At different stages, she turns on the t.v., the radio, gets up, sits down, and makes numerous cups of tea. Most of her time is taken up with moving between rooms, furniture, and mindless tasks, flicking through Hello magazine or finishing some sewing. A couple of times she stands frozen at the sink, staring out the window.

The character's movements would not be so touching if it wasn’t apparent that she lives alone and everything she does seems directed at filling time. Nothing conveys her very modern tragedy better than adding a garnish to a quickly prepared supper for one, before setting the table again with glistening white crockery, seemingly for breakfast.

The character's movements would not be so touching if it wasn’t apparent that she lives alone and everything she does seems directed at filling time. Nothing conveys her very modern tragedy better than adding a garnish to a quickly prepared supper for one, before setting the table again with glistening white crockery, seemingly for breakfast.

Immersing us in the apartment, the production tries to mask its own theatricality in order to bring us close to the character’s predicament. But it’s impossible to expect 17 people to act like ghosts: in fact, this makes us work harder rather than be absorbed more deeply into the action. Perhaps if there was only one spectator present, or we were assigned roles or a specific place within the aparment, this would be less of a problem. For, despite our efforts at discretion on this occasion, we inevitably bump into one another, or Walsh, as we attempt to follow her about the apartment. Trying to downplay theatricality presents other difficulties with the performance too. In Walsh's demeanour and the mundane tasks she performs, there’s nothing to suggest that she is troubled to the point of taking her own life as she eventually does. Even if someone who was planning to kill themselves could possibly behave so coolly as this in her own space, we need her disposition and the risk of suicide to be a bit more clearly signalled early on in order to totally commit for up to 85 minutes in the apartment.

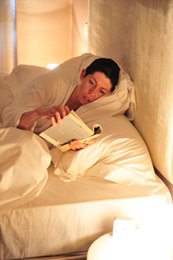

When Walsh first enters, rubbing her belly, and later crying while using the bathroom, we are led to believe that she might be physically unwell, or pregnant. However, the first indication that she is seriously distressed doesn’t come until the last ten minutes of the performance. The few of us who manage to make it into the compact bedroom witness her get into bed and turn off the lights. In the blacked-out space, she starts to cry. That we are all invisible to each other for the first time makes this an intensely affecting moment. Suddenly, she gets up and goes to the kitchen, where she methodically washes down tablets with a small bottle of champagne. Not quite eye-balling us, she glances passively at those present, and the lights go out.

While there is still room in Corcadorca’s site-specific production to refine the spectator’s role, and signal more clearly from the outset what is at stake, with the eminently engaging Walsh playing the central role, the production still succeeds in creating social resonance and emotional impact with Kroetz’s play.

Fintan Walsh