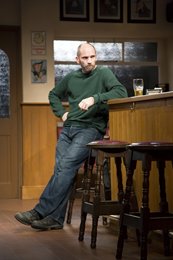

Quietly is a well-written, powerfully performed, close-to-the-bone play about violence and forgiveness. The seventy-minute performance is compelling, from the moment that Jimmy (Patrick O’Kane) says to Robert (Robert Zawadzki), the Polish barman of his local pub, “There’s a man coming in later to see me. There might be trouble” and you know, right there, that there is trouble on its way for sure.

This trouble takes several forms, from the violent headbutt that Jimmy greets Ian (Declan Conlan) with, to the outpouring of bitterness from both men. This is no innocent meeting – Ian has sought out Jimmy to apologise for killing his father in a Loyalist bomb attack on this very pub thirty-six years before. The tension between O’Kane and Conlan is palpable as they mull their pints, debating how and when to plunge into the fray of regret and recrimination. All of this is witnessed by Zawadzki, whose studied indifference provides the others with a necessary audience and potential referee. At the end of the play when it seems Robert may have his own troubles, Zawadzki puts this indifference aside and emerges as a hardman himself.

Though the play is short it tackles the depth of pain and division that still defines Northern Ireland. McCafferty’s writing feels psychologically nuanced and the emotions conveyed through the script and the performances are acutely visceral. Jimmy Fay’s direction is one reason for the success of the show; it is tight and tense for almost its entirety. Philip Stewart’s sound design works brilliantly, particularly in creating the terrifying soundscape as the play ends, and Alyson Cummins’ set has the feel of a refurbished pub, complete with both Bushmills and Guinness signs. All of these factors make this a play to go and see and I hope that audiences will see it, and act as witnesses to this drama.

Though the play is short it tackles the depth of pain and division that still defines Northern Ireland. McCafferty’s writing feels psychologically nuanced and the emotions conveyed through the script and the performances are acutely visceral. Jimmy Fay’s direction is one reason for the success of the show; it is tight and tense for almost its entirety. Philip Stewart’s sound design works brilliantly, particularly in creating the terrifying soundscape as the play ends, and Alyson Cummins’ set has the feel of a refurbished pub, complete with both Bushmills and Guinness signs. All of these factors make this a play to go and see and I hope that audiences will see it, and act as witnesses to this drama.

But I have another, almost as strong reaction to this play too – that it is yet another narrative of men and violence and the north, that stages forgiveness and closure in an unconvincing handshake. Except for plays like Tinderbox’s 'True North' series, Christina Reid’s Tea in a China Cup and Anne Devlin’s Ourselves Alone, the Troubles is consistently framed as a male-dominated narrative. And now the peace process is being framed likewise. While Jimmy and Ian’s stories are compelling, they are remarkably similar to the stories presented in the 2009 film Five Minutes of Heaven. And in both versions of the truth and reconciliation process, women are only presented via the men’s narratives.

Ian’s story of the bomb attack does not end at the moment when he threw the bomb in the door of the pub. After he makes his escape he heads to a Loyalist bar, where he is applauded and, in a coming of age gesture, is bought his first pint, and ushered towards a group of girls and told he can have his pick, “they are doing their bit”. When he approaches one of them, she leads him outside to lose his virginity. The implication of the story is that Ian killed six “Fenian bastards” not because he hated Catholics, but because he wanted to be a man. Decades later he meets that “wee girl” again and she tells him that she became pregnant after their brief sex and had to go to Liverpool to obtain an abortion, something which haunts her. Yet even as Ian narrates this, he claims it as his pain, as an aspect of his personal haunting. The woman is not important – she doesn’t even have a name.

Jimmy talks of his mother’s suffering after his father’s death. But again what is significant in this performance is how his mother’s sorrow makes Jimmy feel. And his mother is not named, just as Robert’s wife and girlfriend are not.

I know – it is unfair to judge this play in these terms, to scapegoat what is a very good play for being symptomatic of a much wider cultural problem. The play, after all, largely achieves what it sets out to do. And yet, how hard can it be to include a female character, to imagine the Troubles through a woman’s eyes? Friel managed it in Freedom of the City and gave that play its most captivating character, Lily. Albeit Lily was a self-sacrificing wife and mother, at least she had an active role and, above all else, a voice and a name.

I know – it is unfair to judge this play in these terms, to scapegoat what is a very good play for being symptomatic of a much wider cultural problem. The play, after all, largely achieves what it sets out to do. And yet, how hard can it be to include a female character, to imagine the Troubles through a woman’s eyes? Friel managed it in Freedom of the City and gave that play its most captivating character, Lily. Albeit Lily was a self-sacrificing wife and mother, at least she had an active role and, above all else, a voice and a name.

There are other issues with the play. Robert doesn’t get much of a look in as a character: though he is attributed with a personal life (via fairly clunky text messages) and subject to sympathy at the end, at times it feels as if his nationality is purely a handy device. Likewise, the football match on in the background between Poland and Northern Ireland, mirroring the 1974 World Cup Poland game that was playing when the bomb exploded, is a little too tidy as a frame, a coincidence too far.

Within the plot, despite the enormous division between the two men, their life experiences, and their roles as victim and aggressor, there is an inexorable move towards closure. This movement seems so vital to plots about truth and reconciliation, and yet is so problematic – it would be enough I think, just to have the truth. This story isn’t over, no matter how many times the referee blows the whistle.

This is a finely written play, and its cast, direction and design are impressive. But the issue that remains to be reconciled, and that is just as important as the reconciliation of men from opposing sides, is the glaring absence of women in too many narratives of the Troubles.

Emilie Pine lectures in drama and film at University College Dublin.