Flying in from the tinselly world of Hollywood movie blockbusters, Cillian Murphy touches down as an avenging angel in the gritty Galway Arts Festival premiere of a new version of Enda Walsh's darkly funny Misterman. In a transformed Black Box Theatre, the powerful forces of Catholic guilt, small-town oppression and dominant Irish mammies work their nasty ways on the vulnerable and weak. Landmark Productions and the Galway Arts Festival’s big budget, big bang is a high-octane dramatic rush.

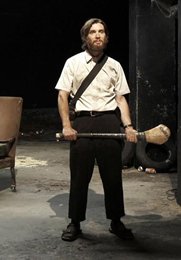

Thomas Magill (a hirsute Cillian Murphy) is a well-meaning evangelist who has an obsession with sin. Sifting through his memory, he repeatedly relives his searches for the heavenly peace that he might expect to come “dropping slow” in his town of Innisfree. Frustrated by all around him, and on the day of the town’s ‘community dance’, Thomas decides to set off on a proselytizing tour of his neighbours. From the ban an tí to the garage mechanic and even to Roger the dog, “sin is our religion” and yet all could be saved if Thomas works hard enough. Lonely, mocked and often thwarted in his mission, Thomas’ zeal is re-charged when the angelic Edel offers to accompany him in his good works...

Thomas Magill (a hirsute Cillian Murphy) is a well-meaning evangelist who has an obsession with sin. Sifting through his memory, he repeatedly relives his searches for the heavenly peace that he might expect to come “dropping slow” in his town of Innisfree. Frustrated by all around him, and on the day of the town’s ‘community dance’, Thomas decides to set off on a proselytizing tour of his neighbours. From the ban an tí to the garage mechanic and even to Roger the dog, “sin is our religion” and yet all could be saved if Thomas works hard enough. Lonely, mocked and often thwarted in his mission, Thomas’ zeal is re-charged when the angelic Edel offers to accompany him in his good works...

In some ways, Enda Walsh’s re-visiting of his 1999 script creates a similar world and ideas to Patrick McCabe’s 1992 novel The Butcher Boy: the audience views (a slightly dated) Ireland through the eyes of a fundamentally flawed soul who, honed by narrow and dogmatic cultural influences, has evolved a rather twisted view of human morality. Similarly too, since the fateful day is revealed and relived through the central character, the realities of the events are suitably ambiguous: is Thomas Magill a bigoted and paranoid delusionist or is his world actually peopled by the wastrels he describes? Do we dislike him for his irascibility with the prosaic nature of everyday life, or do we ache for him in his doomed and ultimately hopeless vision of a heaven on earth? Reality and imagination are deeply and inseparably entwined. Yet despite the potentially gloomy subject material, Walsh’s visceral wit, occasional lyricism and awareness of short attention spans, ensures that this is a work that enjoys delving into the nastier zones of human behaviour with a wild and mischievous exuberance.

This Landmark and Galway Arts Festival production stands out as a very significant piece of theatre making.

As writer and director, Walsh needs to invent a dramatic device in order to let the audience into the inner convulsions of Thomas’s tortured mind. The novelist can use pages of narrative prose; Walsh uses a battery of tape-decks littered about the stage. Each machine repeats voices and sounds from Thomas’ inauspicious day, as he flounders, stumbles or leaps from one machine to another. Sometimes he turns them on; at other times the machines play autonomously and lead him around the stage from one to another. Despite his best efforts (hammering, stamping and hurling the machine across the stage) he finds the tapes continue to harangue him. This is his subconscious working - the whirrings of a mind diseased and tortured by guilt, insecurity and madness. All this while, outside, barely restrained by the steel doors of the Black Box Theatre, a vengeful hound howls at Magill.

As writer and director, Walsh needs to invent a dramatic device in order to let the audience into the inner convulsions of Thomas’s tortured mind. The novelist can use pages of narrative prose; Walsh uses a battery of tape-decks littered about the stage. Each machine repeats voices and sounds from Thomas’ inauspicious day, as he flounders, stumbles or leaps from one machine to another. Sometimes he turns them on; at other times the machines play autonomously and lead him around the stage from one to another. Despite his best efforts (hammering, stamping and hurling the machine across the stage) he finds the tapes continue to harangue him. This is his subconscious working - the whirrings of a mind diseased and tortured by guilt, insecurity and madness. All this while, outside, barely restrained by the steel doors of the Black Box Theatre, a vengeful hound howls at Magill.

Of course, the taped voices (a nod at Beckett) are the means by which Thomas recalls events, reviews them and attempts to understand his own behaviour. Similar to other works by Walsh, when this ‘play within a play’ ceases, when the tapes run out, when Thomas tires of their reeling in the day, then we can anticipate the character’s demise. The entire sensory immersion, with Donnacha Dennehy’s score tying it together, calls for extraordinarily detailed coordination between sound designer (Gregory Clarke), engineer (Helen Atkinson), chief controller (Rachel Murray) and actor, and the technical intricacies are seamlessly handled here.

Designer Jamie Vartan’s bullish, physically overbearing set (a deserted warehouse) seems to emerge from the walls of the Black Box in perhaps one of the best uses of the space in this theatre’s history. Possibly a depiction of Thomas’ warped brain, vast steel joists tower over the audience as they grow from a stained concrete floor. It is a chamber for violence, confusion, histrionics and effects of almost Christopher Nolan-esque proportions. Each section of the set is then transformed by Thomas as he remembers and re-enacts aspects of this day, again and again. His tapes, rickety furniture and a few miraculously-appearing props transform each section into scenes of the day’s excesses:  Swarfega, used as a vapour rub on his half-naked bedbound mother, defines the bedroom; cheesecake defines the coffee-house; the upper reaches of the warehouse structure create the final gruesome image in the disco scene... Since Vartan uses the entire width of the theatre, sightline problems do occur for audience members at the far reaches of the theatre’s bleacher seating, but his conscious blurring of the architecture of the theatre with the structure of the set mimics wonderfully the perplexing intermingling of reality and imagination in the text.

Swarfega, used as a vapour rub on his half-naked bedbound mother, defines the bedroom; cheesecake defines the coffee-house; the upper reaches of the warehouse structure create the final gruesome image in the disco scene... Since Vartan uses the entire width of the theatre, sightline problems do occur for audience members at the far reaches of the theatre’s bleacher seating, but his conscious blurring of the architecture of the theatre with the structure of the set mimics wonderfully the perplexing intermingling of reality and imagination in the text.

Finally, a top-ranking member from the higher echelons of the acting fraternity gets to strut his stuff in a role he allegedly begged Walsh to give him. Whilst this audience pulling-power gives the production a guaranteed sell-out, the casting works. Murphy relishes the swift character changes and the opportunity to use every voice, body and acting contortion conceived by Stanislavsky and beyond. The dance, mimicry, physical japes, even Murphy’s well-known cutesy little-boy act: all are well executed, timed and impeccably judged. One realises why he is so requested: Murphy hits the mark every time.

This production of Misterman is a celebration of technical skill, luscious writing, extravagant acting and high production values. What are Arts Festivals good for? Finding ways to match-make an interesting script to a fine actor, aided by virtuosic technical crew. A summer blockbuster is born. It happens here.

Matthew Harrison is an English Teacher at Coláiste Iognáid, Galway and a regular contributor to arts programmes on RTÉ.