When Denis Kelly’s Love and Money was first produced six years ago, there was prescience in its revelations about early twenty-first century Mammon and its taboo demigod: crushing debt. Indeed, Kelly seems to have been more visionary than many contemporary analysts in throwing the spotlight on the anti-social and self-destructive consequences that would follow rampant consumerism and the associated deification of money. In their choice of this temporally specific play for the Arts Festival, Galway Youth Theatre seem to be attempting to shut the stable door a few years too late. At the same time this group, usually generously energetic, pro-active and boundary-stretching, makes an overly severe, low-risk investment in most aspects of the production, making it seem miserly rather than thrifty.

David (Conor Geoghegan), the play’s Everyman, attempts to strike up a relationship via email and in one of his electronic missives – and one of the play’s more improbable moments – he confesses to the killing of his wife, Jess (Shaunna McEvilly). Needless to say, this chat-up strategy fails. We learn that Jess’s extravagant consumption of anything on the High Street led to the couple’s crippling debt and her attempted suicide. In order to find a way out of their financial deficit, and as she lies in a sleeping-drug-induced coma, David completed her act by tube-feeding her with vodka.

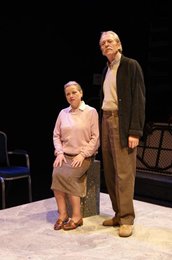

Zipping through a series of flashbacks that take us increasingly into the characters’ pasts and deeper into this century’s moral deficits, we see Jess’s parents (Rod Goodall and Mary Monaghan-McHugh) demonstrating their grief at her grave by desecrating a lavishly constructed neighbouring tomb that they think competes with their daughter’s. We also see David begging a friend for a demeaning job in order to pay for his wife’s increasing abuse of her credit card, then a somewhat extraneous scene (seemingly an illustration of the commodification of a woman and her revenge) between a pornographer (Rod Goodall) and model. Finally we return to the outset of the marriage, with Jess celebrating her engagement by imagining her rush through the shops for the necessary bridal accoutrements. Clearly the rot started early for this modern-day Lydia Bennett.

So, nothing is sacred (or new) in Kelly’s deconstruction of consumerism. To the detriment of everyone, death, sex, work, marriage and even love is costed, not valued. Spicing things up a little, however, and perhaps the selling point of this work, is its fashionable structural twisting of the order of events: we start at the end of the story and end at the beginning. Therefore, scenes do not naturally flow from one event to another and, initially, seem to be unconnected in a mosaic of experiences. Unfortunately, when GYT encounters this inverted chronology, problems are exacerbated.

Fiscally responsible director, Niall Cleary, makes do with a stark, khaki-coloured stage in the round, where a few similarly painted blocks are all that are used to establish the world of the play: they serve as tables, chairs, tombs, and shop-fronts amongst others. Imaginative and well-nuanced live music created by the troupe and guitarist Robbie Carroll fills in some of the rather depressing social background, and Cleary always ensures that the text is treated sensitively and appropriately. However, for this particular narrative structure, the nondescript nature of the stage furniture and the sparse set hardly help the audience locate or contextualise the action, differentiate between scenes, or even permit helpful stage business for the performers. In a similarly confusing fashion, at least one actor doubles parts and so at times we assume that others also change roles throughout the play. What was intended as an interesting structural device becomes merely puzzling.

Fiscally responsible director, Niall Cleary, makes do with a stark, khaki-coloured stage in the round, where a few similarly painted blocks are all that are used to establish the world of the play: they serve as tables, chairs, tombs, and shop-fronts amongst others. Imaginative and well-nuanced live music created by the troupe and guitarist Robbie Carroll fills in some of the rather depressing social background, and Cleary always ensures that the text is treated sensitively and appropriately. However, for this particular narrative structure, the nondescript nature of the stage furniture and the sparse set hardly help the audience locate or contextualise the action, differentiate between scenes, or even permit helpful stage business for the performers. In a similarly confusing fashion, at least one actor doubles parts and so at times we assume that others also change roles throughout the play. What was intended as an interesting structural device becomes merely puzzling.

Similarly strange is the decision to cast the experienced and well-known (Rod Goodall and Mary Monaghan-McHugh) amongst GYT regulars. Goodall’s voice projection alone, for example, contrasts starkly with the efforts in this area by other excellent but less trained co-performers. The decision also highlights the limited use of one of GYT’s most distinctive resources: a large, young, hard-working and low-cost workforce. Historically, GYT has either splurged that capital (which is generally out of reach of most fully professional companies) by staging vastly populated and enormously energetic ensemble pieces, or allowed it the ability to speculate in ground-breaking site-specific shows for tiny audiences. This production, unfortunately, dips into little of this underlying wealth, and the resultant show is a rather staid one for this otherwise innovative troupe.

Matthew Harrison