Time heals, they say. Not in the Martin family, it doesn’t: twenty-five years after leaving Belfast inexplicably, the errant Billy returns, unleashing in his father and three sisters the emotions, fears and frustrations coiled to snapping point in the quarter-century of his absence. A can of worms being opened? More a nest of poisoned vipers suddenly released from captivity, stinging and maiming any unfortunate victim in their pathway.

The Martin family in question is, of course, that of Graham Reid’s so-called 'Billy trilogy', a series of plays written for BBC television in the 1980s. They made a remarkable impact at the period, their depiction of a Protestant working-class family torn apart by infidelity, drink, and raging emotional conflict striking deep chords in the collective psyche of the Northern Irish viewing public, and stunning mainland audiences by powerfully demonstrating that people living in Belfast could have 'ordinary' problems too, not just those arising from the Troubles.

.jpg.aspx%3Fwidth=260&height=172)

In Love, Billy, the fifth play in the Martin saga, and the first written specifically for the theatre, Reid investigates what happens when the family is unexpectedly reunited for father Norman’s seventy-third birthday. It is not a pretty picture. Norman has had a stroke; once “the hardest man in Belfast”, he now spends much of his time motionless in an armchair. His eldest daughter Lorna (who had a play to herself in 1987) is a traumatised RUC widow; her husband, a Catholic policeman, had his brains blown out in a sectarian incident. The two younger daughters, raised in England by a stepmother, are a potty-mouthed nurse on her third marriage, and a religious zealot given to serial Bible study and quoting scripture.

And Billy? He’s a serial philanderer who drives a lorry for a living. He has a sign with his mother’s name on it in the cab window, and once spent time in South Armagh as an undercover agent with the British Army. Norman’s English wife Mavis (the consistently sympathetic Ger Ryan) is a saintly figure, calming her husband’s instant apoplexy whenever Billy’s name is mentioned, and tending to his mobility issues with patient devotion.

Love, Billy is built on violent verbal confrontations and eructations, some of which are more effectively realised than others. Norman is vividly three-dimensional in George Shane’s detailed and sensitive performance, but too many of the bilious outbursts against his son turn into fevered ranting, with an alienating effect opposite to the one intended.

Billy’s animus towards his father is, on occasion, equally grinding. That he can’t forgive him for not visiting his first wife (Billy’s mother) when she was dying in hospital is, possibly, comprehensible. To ferociously rehearse the argument again in public, when he has taken his ailing father in a wheelchair to view the site of the old family home in Coolderry Street, seems simply incredible, both dramatically and on a human level. The scene seems mawkishly implausible and unnecessary.

There’s also a surprising amount of political content in Love, Billy, something largely absent from its four predecessors. Lorna is given a long, bitter monologue demonising local politicians and bemoaning the transformation of the RUC (of which she was once a member) into the PSNI, which she clearly views as a lily-livered political compromise by comparison. This is uncomfortable water to tread in, even in the relativestability of modern, post-conflict Belfast, and adds relatively little to what we already know about Lorna and her situation. Maggie Hayes copes well enough with the writing, but often strikes a slightly hesitant, uncertain note in her overall depiction of the character.

Ann and Maureen, the younger sisters, are colourfully played by Tracey Lynch and Sarah Lyle respectively. Ann is comfortably the better-written character, her sharp-tongued wise-cracking and basic warmth of nature contrasting starkly with the rigidly correct demeanour of her starchily devout sister. Frustratingly, we learn nothing about where Maureen’s religiosity comes from – odd, given the detailed attention to backstory Reid confers on other characters.

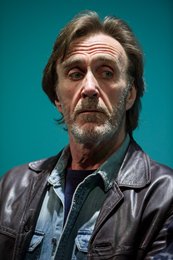

Billy himself, for all the grief he visits on those around him, remains a strangely shadowy, elliptical figure, who yields his own personal history with grudging partiality. Actor Joe McGann deploys a fair amount of shoulder-shrugging and ironic sighing to indicate bemusement at the degree of upset his heedless conduct down the years has caused the family. Occasionally you sympathise with him: the emotional issues involved in Love, Billy are real and serious, but the characters involved do amazingly little to actually resolve them in anything approaching a grown-up, adult fashion.

And that’s the problem with Love, Billy – the dysfunctions of the Martin family are so rigidly embedded that change on an individual level is excruciatingly difficult, and collective resolution virtually impossible. So for all the hyperactive arguing and vigorous emoting that fill the two hours’ stage time, the play seems curiously static and obdurately non-developmental.

There’s a reconciliation of sorts at the end, when Billy kisses his dead father lightly on the head, in a drably furnished hospital waiting area. It’s virtually the only time he shows him any tenderness, however: the kiss seems thinly motivated, a sentimental rather than genuinely meaningful gesture.

David Craig’s set is unobtrusively functional, a modern middle-class interior with Norman’s bedroom visible above it, and a kitchen area stage-right, where some of the more intimate conversations happen. Roy Heayberd’s direction deftly replicates the finely honed conversational rhythms of Reid’s script, and neatly choreographs relationships between the characters. That they are all still damaged goods at the play’s conclusion is not his fault. For the Martin family at least, it seems, loose ends are only ever tied up partially, and while personal circumstances change markedly with the passing of the years, old problems die hard, the individuals involved in them remaining basically the same as ever.

Terry Blain is an arts journalist and cultural commentator, contributing regularly to BBC Music Magazine, Opera magazine, the Belfast Telegraph, Culture Northern Ireland and BBC Radio Ulster.