Fregoli Theatre’s premiere of Rory O’Sullivan’s kinetic script is underwritten by counterpoint. As we take our seats, Joe (Aron Hegarty) lies flat on his back, his head cradled in the lap of a kneeling Anna (Kate Murray), her head bowed towards his. The meticulous stillness maintained by both actors during this extended tableau is relentlessly exploded by the blistering voltage that ensues. Behind them, a barbed-wire fence is embroidered with purple petals in an incongruous image that succinctly encapsulates this production’s marriage of brutality and tenderness.

As a baby floating in a basket down the Liffey, Joe was plucked from the river and sent to live with the sinister Storyman. Locked in darkness, Joe is joined by Anna, a young girl taken from her family. In adolescence, they escape but their childhood bond is obliterated by the fury of their bitterness, with Joe engaging in violent crime while Anna enters prostitution. When Joe and Anna’s lives intersect as adults and they embark on a tentative date, they unwittingly find themselves outside the house in which they were incarcerated and are forced to confront their harrowing past.

As a baby floating in a basket down the Liffey, Joe was plucked from the river and sent to live with the sinister Storyman. Locked in darkness, Joe is joined by Anna, a young girl taken from her family. In adolescence, they escape but their childhood bond is obliterated by the fury of their bitterness, with Joe engaging in violent crime while Anna enters prostitution. When Joe and Anna’s lives intersect as adults and they embark on a tentative date, they unwittingly find themselves outside the house in which they were incarcerated and are forced to confront their harrowing past.

Hegarty imbues Joe with a fearsome intensity in an elastic performance that reconciles Joe’s mercurial duality: we are as convinced of his spittle-flecked anger when he viciously attacks a “kiddie fiddler” as we are of his fumbling, endearing nervousness around Anna on their date. The touchstone of Murray’s sensitive portrayal of Anna is her character’s haunting refusal to acknowledge that she can’t reclaim her desecrated childhood; Murray snapshots Anna’s pervading grief while confidently unfurling how it expresses itself as incandescent rage. Hegarty and Murray channel the multiplicity of voices encountered by Joe and Anna and the actors persuasively navigate their characters’ journey from young children to adults.

Co-directors Rob McFeely and Maria Tivnan stamp this highly physical production with minutely-calibrated choreography. In various stages of Joe and Anna’s lives, in both their intimacy and estrangement, Hegarty and Murray frequently shadow or orbit each other in a brittle, fluid waltz. The production’s moody lighting repeatedly invokes the crack of light (in a darkened room) that embossed Anna’s childhood to underscore her persistent groping to restore her lost innocence. The lighting design is striking in its stark illumination of Joe’s face as he hears Anna being sexually assaulted.

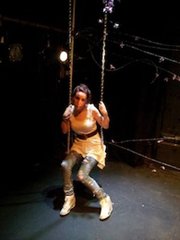

Rebecca Ryan dresses Joe in a tracksuit bottom, hoodie, and a sleeveless denim jacket and Anna in jeans and a white dress. Anna’s purple belt meshes with the production’s overall hue: purple petals are threaded through the metal swing that hangs stage right and the barbed-wire fence that undercuts the ostensible safety of this playground. As the play reaches it elegiac climax, Anna is doused in a shower of purple petals that fall from the sky.

Rebecca Ryan dresses Joe in a tracksuit bottom, hoodie, and a sleeveless denim jacket and Anna in jeans and a white dress. Anna’s purple belt meshes with the production’s overall hue: purple petals are threaded through the metal swing that hangs stage right and the barbed-wire fence that undercuts the ostensible safety of this playground. As the play reaches it elegiac climax, Anna is doused in a shower of purple petals that fall from the sky.

Weaving influences as diverse as Taxi Driver and Disco Pigs, O’Sullivan’s script seems to scupper the expectations it initially generates. If its opening premise resonates with murkier chapters in recent Irish history, this is never explored, while potential themes of the plight of the marginalised or of accommodating yourself to a poisoned past are displaced by a budding love story. More significantly, the writing’s flow is stifled by the characters’ insistence on describing their actions – even as they perform them – for the audience.

Despite this, Fregoli’s depiction of the inner turmoil of two broken lives lingers and there is genuine pathos in Anna’s “dream of an ordinary life” and in Joe’s daily’s conundrum: “How will I get through today?” This evocative, pulsing production echoes the lyricism of O’Sullivan’s script (“music like dripping gold”, “teabag-coloured curtains”) and spotlights the emergence of a promising playwright.

Brendan Daly is a freelance arts journalist and critic for publications in Ireland and the U.S.