Almost two years after the centenary celebration of Bacon’s birth in 1909, his name(s) makes a welcome return in Brian McAvera’s latest work, Francis & Frances.

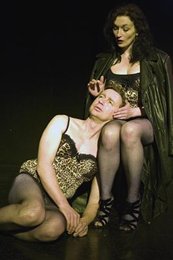

In a play about the life and work of Francis Bacon (and his alter-ego Frances), one might expect to see something of the speckled disarray of the artist’s infamous matchbox studio reproduced in a theatre space that is similarly diminutive and confined, but set designer Sarah Jane O’Neill chooses instead to embellish the walls of the stage with bits of broken mirrors, reflecting the audience as an image of a kind of Baconesque distortion. Against the backdrop of our own disfigured image, a torrential stream of dialogue (punctuated by ten ‘propositions', one of which reads: “there is no life after death”) unfolds between the leather-clad, leopard-printed Francis (Cathal Quinn) and his matching dominatrix alter-ego, Frances (Tara Breathnach).

McAvera endeavours to elucidate the brutal truth about Bacon’s mysterious and brilliant artistic world by exploring a string of non-chronological events plucked from the artist’s life and played out in semi-biographical ‘scenes.’ Colm Maher’s lighting makes an immediate impression in creating contrasting atmospheres, while Sonya Deegan’s debut on sound demonstrates finesse for clearly underscoring time and place throughout.

Bound by the suggestion that Francis and Frances are the title-roles in their own impromptu movie, the irregularity of the ‘scenes’ soon becomes an apt feature of this wildly spontaneous and rather disturbing insight into the artist’s Godless vision of a violent, gruesome and chaotic world. On a broader level, when we witness Francis in an effective physical confrontation against an invisible force - as well as his references to himself in the past rather than the present tense – it may be that McAvera is challenging the opening proposition that there is no life after death, and Bacon’s belief that “we are born and we die and that’s it.”

Although a fairly humorous play (with Quinn’s one-on-one striptease to a mortified audience member being the most memorable occasion), McAvera’s chromatic text penetrates the bigger darker themes around the artist’s predilection for the grotesque, his acute obsession with death and decay, and his tendencies towards sadomasochism – themes that are inherent in most, if not all of his paintings. Francis and Frances characterize the spectrum of Bacon’s difficult life and the people in it by morphing from one character to the next in swiftly shifting sequences throughout the two-hour play, with the fluidity and clarity of the changes in the actors’ voices and bodies ensuring our interest is maintained from beginning to end. Through them we meet Bacon’s British-born parents, Anthony and Christina, in a sharply satirical vignette of their wedding day, and, more poignantly, we encounter Bacon as a child, dressing up in his mother’s underwear, playing with shrapnel in the street, and being forced to mount a horse by his dictatorial father, despite the child’s violent allergy to the animal.

Although a fairly humorous play (with Quinn’s one-on-one striptease to a mortified audience member being the most memorable occasion), McAvera’s chromatic text penetrates the bigger darker themes around the artist’s predilection for the grotesque, his acute obsession with death and decay, and his tendencies towards sadomasochism – themes that are inherent in most, if not all of his paintings. Francis and Frances characterize the spectrum of Bacon’s difficult life and the people in it by morphing from one character to the next in swiftly shifting sequences throughout the two-hour play, with the fluidity and clarity of the changes in the actors’ voices and bodies ensuring our interest is maintained from beginning to end. Through them we meet Bacon’s British-born parents, Anthony and Christina, in a sharply satirical vignette of their wedding day, and, more poignantly, we encounter Bacon as a child, dressing up in his mother’s underwear, playing with shrapnel in the street, and being forced to mount a horse by his dictatorial father, despite the child’s violent allergy to the animal.

Other pivotal episodes in Bacon’s early life – his struggle to come to terms with his homosexuality against his father’s heavy-handed condemnation, and being locked in a cupboard while his babysitter had sex with her boyfriend – find tender expression in the interactions between Breathnach and Quinn, particularly where a mother-son relationship is momentarily suggested. It is in these instances that the Bacon we meet in the play’s disquieting opening – he who lets out a long unsettling roar and announces how he still masturbates – is better understood.

The tension between Francis and Frances – the latter being the self he has repressed, equipped with whip at all times and not afraid to use it – is never far from erupting, as the characters transform again and the self-torturing cross-examination of Bacon’s inner mind resumes, playing on feelings of guilt, humiliation, isolation and deep despair at being misunderstood.

Although there is immediate physical semblance between Quinn and the late Bacon – further enhanced by Quinn’s imitative hand gestures and effeminate gait characteristic of the artist – McAvera’s direction has generated a rather excessive sense of self-glorification and grandiosity in Francis, features that are not entirely faithful to the unassuming and somewhat nervous man we see in the archival recordings. Breathnach’s presence on stage is consistently cool and controlled, despite her brief loss of whip in the opening scene, and her continuous shape-shifting throughout, like Quinn’s, is handled with authority.

Jennifer Lee holds an MPhil in Theatre and Performance and is currently completing her PhD thesis.