It’s twenty years since Friel’s play first astonished audiences and, to judge by this Second Age production, the passage of time has facilitated a further unearthing of its riches. If the first encounter with Maggie’s dance is like a first kiss (nothing ever quite as memorable; never ever quite the same again), a revisiting of Lughnasa offers the compensation of a more detached and objective view of the play.

David Horan’s sensitive and compelling production is about clarity. He captures the almost imperceptible disintegration in a place where the household gods of domesticity and stability prevail: each one of the five Mundy sisters tending to their allotted chores in an atmosphere of harmony and affection, economic and spiritual well-being, captured by the stillness of the figures in the opening tableau.

But, as Michael says, “things [are] changing too quickly”: the security of the fireside is under threat, as is the religious and social status quo. There are forces of paganism abroad – both in the stories Father Jack brings home from Uganda and in the rumours of wild things happening in the back hills (Horan underlines the correspondence between these two, by emphasising the language that both scenarios have in common: “dance”, “fire”, “sacrifice”, “goat”) – and technology intervenes, firstly in the sporadic eruptions of Marconi, the radio, and secondly in the opening of the glove factory that destroys the livelihood of Rose (Maeve Fitzgerald) and Agnes (Kate Nic Chonaonaigh). Even the boy Michael senses the unease as his father, Gerry (Stephen Swift) appears, with his jaunty ballroom gait and hollow promises of a bicycle for his son, and then promptly fades into his other life.

But, as Michael says, “things [are] changing too quickly”: the security of the fireside is under threat, as is the religious and social status quo. There are forces of paganism abroad – both in the stories Father Jack brings home from Uganda and in the rumours of wild things happening in the back hills (Horan underlines the correspondence between these two, by emphasising the language that both scenarios have in common: “dance”, “fire”, “sacrifice”, “goat”) – and technology intervenes, firstly in the sporadic eruptions of Marconi, the radio, and secondly in the opening of the glove factory that destroys the livelihood of Rose (Maeve Fitzgerald) and Agnes (Kate Nic Chonaonaigh). Even the boy Michael senses the unease as his father, Gerry (Stephen Swift) appears, with his jaunty ballroom gait and hollow promises of a bicycle for his son, and then promptly fades into his other life.

The second half of the play, in particular, brings home the fragility of the human condition. Through his cast, Horan points this up superbly. In Charlie Bonner (Michael), he has a commanding narrator who, with a voice tempered by an authentic Donegal ‘burr’, contemplates that summer of ’36, not only telling the story but capturing the emotional atmosphere of the events. Nowhere is this more affecting than in his account of the sad end of the two sisters who emigrated into the oblivion of the Irish diaspora. He is the filter of the memories.

Garrett Keogh’s Father Jack, who may be suffering the culture shock of coming home after a lifetime in Africa, is neither mad nor bad, but perhaps sad for the lost world of instinctive, sensuous human interaction that he has left behind in Ryanga and which has been suppressed in DeValera’s Ireland. Keogh’s performance is impressive – making the character both intelligible and credible.

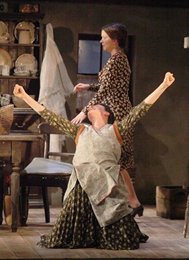

In Donna Dent Horan has found a Kate who can encompass the tensions between control and release, between a dutiful commitment to duty and an abandonment to instinct. She is shocked by her own flashes of raw emotion, wonderfully conveyed in ‘the’ dance when she hesitates, holds back, frowns, draws her whole body in, relents, yelps, throws herself into the frenzy and then withdraws to the yard, where she tries to make sense of it all.

Starting in a precise, workmanlike mode, the production gathers a momentum, which becomes emotionally charged. Maree Kearns’ set contrasts the domestic trimness of the Mundy kitchen with the disorderly uncertainty of the garden beyond – unruly bushes and straggling stone walls; Leonore McDonagh’s costumes, if a little too redolent of Laura Ashley, evoke the period precisely. The dancing of the title is a central motif, articulated through the choreography of Muirne Bloomer. Her work with Gerry and Chris (Marie Ruane) is almost too spectacular. The dance that escalates as the radio signal swells is suitably dervish-like and, if Susannah de Wrixon’s Maggie didn’t quite have the carnal fervour of Anita Reeves’ electrifying original, her singing voice proves to be a superb conduit for the poignancy of the piece when she sings The Isle of Capri.

Starting in a precise, workmanlike mode, the production gathers a momentum, which becomes emotionally charged. Maree Kearns’ set contrasts the domestic trimness of the Mundy kitchen with the disorderly uncertainty of the garden beyond – unruly bushes and straggling stone walls; Leonore McDonagh’s costumes, if a little too redolent of Laura Ashley, evoke the period precisely. The dancing of the title is a central motif, articulated through the choreography of Muirne Bloomer. Her work with Gerry and Chris (Marie Ruane) is almost too spectacular. The dance that escalates as the radio signal swells is suitably dervish-like and, if Susannah de Wrixon’s Maggie didn’t quite have the carnal fervour of Anita Reeves’ electrifying original, her singing voice proves to be a superb conduit for the poignancy of the piece when she sings The Isle of Capri.

And if Dancing at Lughnasa is about music transcending words, and holding so much charged emotion – longing, abandonment, tenderness – if it’s about dance in all its shapes and forms, it’s also about language: even as Michael describes “language surrendering to movement” and Jack, rediscovering his English vocabulary, evokes the ritual dances at Ryanga, it is ultimately the playwright who weaves the magical poetic "mirage of sound" that makes Lughnasa such a mesmerizing piece.

Yet, the play is also about the power of silence. The final moment is transcendingly beautiful, in the delicate timing of the fade-out of the silhouetted figures to reflective darkness. And only when the audience has had an opportunity to savour that atmosphere do the lights edge up for the curtain call.

Derek West saw Patrick Mason’s original production of this play at the Abbey and subsequently in Glenties, Co. Donegal, home of Brian Friel’s aunts, upon whom the Mundy sisters are based.