Almost eighteen years may have passed since the paramilitary ceasefires were called, but an uneasy, simmering peace continues to hang over Northern Ireland. From time to time, particularly during the summer Marching Season, evidence of the alienation and marginalisation felt within the loyalist communities rears its head. But in the ranks of republicanism, too, there is profound internal disaffection, much of it emanating from the bitterness felt in some quarters towards those designer-suited politicians who stalk the corridors of power at Stormont and are judged as having sold out the armed struggle.

Those who remain focused on pursuing a militant agenda are generally referred to as dissidents, but writer Sam Millar, himself a former IRA prisoner and blanket protestor, refuses to label them in that way, implying that yesterday’s dissident may be today’s government minister. This is the first play in the 'Ulster Trilogy', Green Shoot’s intriguing state-of-the-nation theatrical audit of where Northern Ireland stands today. Its aim is to lift the lid on deep-rooted resentments, which sometimes rage within the same family, and, in the process, to invite the wider public to engage in a process of examination and consideration.

Those who remain focused on pursuing a militant agenda are generally referred to as dissidents, but writer Sam Millar, himself a former IRA prisoner and blanket protestor, refuses to label them in that way, implying that yesterday’s dissident may be today’s government minister. This is the first play in the 'Ulster Trilogy', Green Shoot’s intriguing state-of-the-nation theatrical audit of where Northern Ireland stands today. Its aim is to lift the lid on deep-rooted resentments, which sometimes rage within the same family, and, in the process, to invite the wider public to engage in a process of examination and consideration.

It marks a stage debut for Millar, an established crime novelist and writer of short stories, who, in his programme note, quotes from Tennessee Williams’s foreword to Sweet Bird of Youth: “I can’t expose a human weakness on the stage unless I know it through having it myself”. The quote would appear to be entirely apposite, since the blunt, unadorned tone of the writing suggests authentic first hand knowledge of the experiences which haunt his central character Frank Mullan.

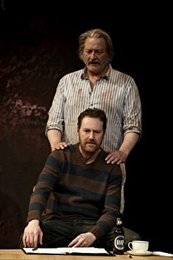

In the hands of veteran playwright Martin Lynch, who here directs, there is precious little that is challenging about the play’s structure and narrative. Most of the action takes place in a single location, the parlour of the Mullan home, where revered old republican Sean Mullan reposes in his coffin. Characters come and go, paying their respects or indulging in a spot of soul searching - his sons Frank and Michael, his widow Norah and his brother Peter, an inveterate charmer, forever with a song on his lips and a woman in his sights. But the piece does not move beyond the hate-fuelled verbal battles, which rage between James Doran’s Frank, a man with the ability to lower temperature, conversation and light levels when he enters a room, and Tony Devlin’s knife-sharp Michael, an upwardly mobile blue-eyed boy, glibly parroting the party line.

.jpg.aspx%3Fwidth=260&height=173) If any further clue as to political context and motivation were needed among the broad invective and sly humour - the latter nicely handled by BJ Hogg’s wise-cracking Peter - it is to be found in David Craig’s set design, comprising an overblown, crumpled and bloodstained fragment of the 1916 Proclamation of Independence. Functioning as a dividing wall of the room, it incorporates a half-open doorway, through which a beam of light casts the shadow of its lofty words, writ large across the polished floor.

If any further clue as to political context and motivation were needed among the broad invective and sly humour - the latter nicely handled by BJ Hogg’s wise-cracking Peter - it is to be found in David Craig’s set design, comprising an overblown, crumpled and bloodstained fragment of the 1916 Proclamation of Independence. Functioning as a dividing wall of the room, it incorporates a half-open doorway, through which a beam of light casts the shadow of its lofty words, writ large across the polished floor.

Doran’s Frank is a ticking time bomb, a gloomy figure, reliant on drink and anti-depressants to control the gruesome memories of his time in the H-blocks and racked with contempt for the perceived treachery of his younger brother, towards whom he cannot glance without exploding. But excellent actor though Doran is, even he can’t coax any credibility out of Frank’s solitary sentimental outpourings over his father’s body, when the truth about what he really did or didn’t do during his 14-year jail sentence starts to seep out. And there is a logistical problem in that the audience’s awareness of the psychological damage he has suffered – and is still suffering - diminishes the balance and viability of his blinkered argument.

Helena Bereen gives a curiously one note, non-reactive performance as Norah, a woman worn out by an unhappy marriage to a man who was not all he seemed and by a lifetime of unquestioning devotion to the republican cause. She has become so devoid of emotion that she mutely soaks up the last wounding insult hurled at her by Frank, while an audible gasp is heard around the auditorium. It becomes pretty evident early on that there is going to be only one way out of this political and domestic impasse, but an abrupt, clumsy ending completely detracts from what might have been the single moment of high drama. One thing is certain, however. A conversation has begun, from which nobody will walk away with nothing to say, no opinion to offer.

Jane Coyle is a Belfast-based freelance arts journalist and critic, who also contributes to The Irish Times, The Stage, Culture Northern Ireland and BBC Radio Ulster.