Overheard while leaving the Gaiety theatre in November 2011: “It was a different time then than it is now.” When Garry Hynes directed Big Maggie on the Abbey stage with Marie Mullen in 2001, I recall thinking (and writing) something very similar. Maggie Polpin’s virtually sociopathic disavowal of sentiment and adherence to austerity and pragmatism seemed remote to the early noughties. John B. Keane’s chilling 1969 savaging of the clichéd Irish mammy didn’t seem to make a lot of sense then, except as a kind of museum piece. Not so much now, though. No. Now watching Maggie sticking rigidly to her plan with an all-too-keen eye on her economic situation, refusing each entreaty from her seemingly blameless but actually kind of deluded children to get their share from a nonexistent kitty, we see her ascension to a true archetype of Dark Mother Ireland.

Keane’s play depicting how a widow systematically alienates each of her four children after taking control of her late husband’s farm and shop was always about exploding comfortable notions of the nurturing matriarch. The Irish mother had long been associated with either a warm and fuzzy tolerance for all her children’s failings or with politicised martyrdom, neither of which Keane gave room to breathe in his creation of Maggie Polpin. She’s “a dab hand at breaking spirits” as the Old Woman (Nancy E. Carroll) observes, and that, sadly enough, is very much true of Mother Ireland herself right now.

Keane’s play depicting how a widow systematically alienates each of her four children after taking control of her late husband’s farm and shop was always about exploding comfortable notions of the nurturing matriarch. The Irish mother had long been associated with either a warm and fuzzy tolerance for all her children’s failings or with politicised martyrdom, neither of which Keane gave room to breathe in his creation of Maggie Polpin. She’s “a dab hand at breaking spirits” as the Old Woman (Nancy E. Carroll) observes, and that, sadly enough, is very much true of Mother Ireland herself right now.

With his characteristic combination of keen observation for the authentic rhythms of the parochial and a low level of tolerance for obfuscation, Keane frequently built powerful and resonant drama from misleadingly everyday situations, and his apotheosis in the hands of Hynes and Druid has made the former ever more clear. His work was and remains successful on the amateur circuit precisely because any of his characters are like people you could meet in any parish hall. Yet like Maggie Polpin, or The Bull McCabe, or Dinzee Conlee, there is also a quality of towering classicism to many of them that has allowed them to endure. This Maggie makes absolute sense for now, and, as audiences titter at her put-downs and sneakily admire her tenacity, they are facing the intractable Ireland that once again sees making its children do what they have to instead of what they want, or driving them away, as its only means of survival.

Apropos as the context may therefore be, this production is grounded by a relatively modest if still stylized aesthetic that allows the humanity of its characters to come through in Keane’s idiom. Francis O’Connor’s set makes use of a black-on-black lattice to frame the opening graveyard scene, then serve as the back and front of the Polpin shop, and with a few modest props and very limited use of bright light and colour, makes the actors pop out. Aisling O’Sullivan conveys that vital sense of the ordinariness of Maggie, complete with a heavy Kerry accent, though she also maintains the terrifying resoluteness that makes this one of the most significant roles written for a leading lady on the Irish stage. O’Sullivan also works well in ensemble though, measuring and adjusting her engagements with the other actors so that each scene is alive as a human confrontation. Keith Duffy draws a few pantomime hoots in his role of freewheeling lothario, and maybe overplays it a bit, but otherwise one of the joys of this production is watching how O’Sullivan’s Maggie works with each of the other characters.

Apropos as the context may therefore be, this production is grounded by a relatively modest if still stylized aesthetic that allows the humanity of its characters to come through in Keane’s idiom. Francis O’Connor’s set makes use of a black-on-black lattice to frame the opening graveyard scene, then serve as the back and front of the Polpin shop, and with a few modest props and very limited use of bright light and colour, makes the actors pop out. Aisling O’Sullivan conveys that vital sense of the ordinariness of Maggie, complete with a heavy Kerry accent, though she also maintains the terrifying resoluteness that makes this one of the most significant roles written for a leading lady on the Irish stage. O’Sullivan also works well in ensemble though, measuring and adjusting her engagements with the other actors so that each scene is alive as a human confrontation. Keith Duffy draws a few pantomime hoots in his role of freewheeling lothario, and maybe overplays it a bit, but otherwise one of the joys of this production is watching how O’Sullivan’s Maggie works with each of the other characters.

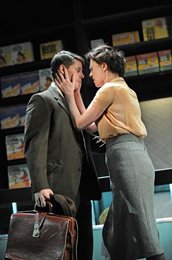

The confrontation between Maggie and eldest daughter Katie (Charlie Murphy) is electric. Hynes blocks the scene to create physical parallels in how the women carry their bodies, and how they stand against the set. Then, as Maggie turns the screws on Katie telling her she was seen with a married man, Murphy turns to face O’Sullivan, and the tension rises before O’Sullivan lunges with real conviction and violence – “Have I raised a whore?” – then pulls back with the devastating, tender observation that she was wrong and that Katie is still a child. There are many such moments, each finely tuned by cast and crew.

The confrontation between Maggie and eldest daughter Katie (Charlie Murphy) is electric. Hynes blocks the scene to create physical parallels in how the women carry their bodies, and how they stand against the set. Then, as Maggie turns the screws on Katie telling her she was seen with a married man, Murphy turns to face O’Sullivan, and the tension rises before O’Sullivan lunges with real conviction and violence – “Have I raised a whore?” – then pulls back with the devastating, tender observation that she was wrong and that Katie is still a child. There are many such moments, each finely tuned by cast and crew.

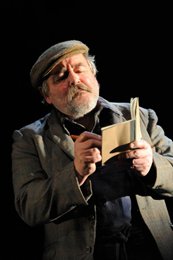

John Olohan draws many of the biggest laughs as the monumental sculptor whose character remains closest to something more obviously caricaturish, and for whom Maggie holds nothing but contempt. Sarah Greene achieves just the right balance of girlish and adult as Gert, with Paul Connaughton a convincingly frustrated Maurice and Stephen Mullan a suitably angry Mick whose brief scenes include an all-too-understandable grab for the cash box that makes more sense now than anyone would like to admit.

Dr. Harvey O'Brien lectures in Film Studies in University College Dublin.