The most remarkable aspect of Frank McGuinness’s monologue play is its ability to implicate an entire society while focusing on a lone soul torn asunder by an act of familial violation. While the centerpiece of Baglady’s fragmented narrative is the eponymous character’s rape at the hand of her father, the spectral figures of Catholic Ireland’s clergy haunt the periphery, blaming the victim and burying any evidence of the crimes committed. The resonances with widespread allegations of systemic child abuse within Irish society as a whole are unmistakable here. Baglady’s (Maria McDermottroe) fraught attempts to exorcise her troubled past also holds a mirror up to the contentious debate about how Ireland can best come to terms with its own history of child abuse. Obviously McGuinness’s play, originally staged in 1985, is not a direct response to recent revelations. However, the fact that it effectively incorporates a societal complicity in the covering up the violence Baglady suffered, while avoiding outright polemics, deepens the play’s impact.

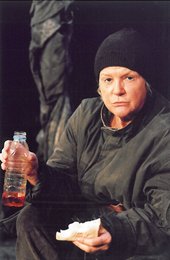

There is a Beckettian edge to director Caroline FitzGerald’s production that, thanks in part to McGuinness’s powerful, minimalist approach to language and staging, can’t really be avoided. Center stage of the newly renovated Focus Theatre is taken up by what appears to be thin tree trunks stretching up the ceiling. Grey is the predominate chromatic tone of Barbara Bradshaw’s design, and the homeless figure of Baglady herself is bundled up in bulking blacks and greys, echoing to some extent the tramps of Waiting For Godot. While all this provides a striking image at the start, it becomes clear, as Baglady attempts to negotiate the space, that the grove of abstract trees at center serves more as a hindrance than a help to the performer.

There is a Beckettian edge to director Caroline FitzGerald’s production that, thanks in part to McGuinness’s powerful, minimalist approach to language and staging, can’t really be avoided. Center stage of the newly renovated Focus Theatre is taken up by what appears to be thin tree trunks stretching up the ceiling. Grey is the predominate chromatic tone of Barbara Bradshaw’s design, and the homeless figure of Baglady herself is bundled up in bulking blacks and greys, echoing to some extent the tramps of Waiting For Godot. While all this provides a striking image at the start, it becomes clear, as Baglady attempts to negotiate the space, that the grove of abstract trees at center serves more as a hindrance than a help to the performer.

Likewise, FitzGerald’s insistence on needlessly breaking up the action at times with Baglady circumnavigating the space dulls rather than sharpens the play’s edge. This is unfortunate, as it’s otherwise clear that FitzGerald and McDermottroe have crafted a focused and finely textured approach to performance. Again, the resonance here is unmistakably Beckettian: the tight and deliberate physical movements of McDermottroe’s Baglady also recall the disciplined and punctuated physicalizations of some of Beckett’s characters.

Despite these parallels, McGuinness’s language is distinctive and powerful, and its almost monosyllabic beat is handled masterfully by McDermottroe, whose subtlety of characterization lends Baglady a gravity that she could easily be robbed of in less skilled hands. It’s obvious from the play’s first line that Baglady has experienced a profound disconnection from concrete reality, but McDermottroe resists playing an overblown caricature of mental instability. Rather, she works throughout the play to build with great care and attention an interlocking logic to Baglady’s own fractious internal reality. As a result, McDermottroe’s performance is measured, taught, and ultimately arresting, a striking portrait of an identity nearly dissolving itself.

And it’s the slippage between the figures and identities that Baglady has absorbed within herself that McGuinness handles with deftness. As she wades through the shattered images of a privileged childhood upturned by her father’s  abuse, Baglady snatches at any likeness that adequately reflects her own lost identity. Instead she’s met with monstrous apparitions of her father, her mother, and the priests and nuns who condemn her to a living death, bearing home the insidious ways in which abuse can find means of expression within its own victims. The simplicity of McGuinness’s stage images open up ritualized spaces for these figures to occupy: the introduction of a bottle of red lemonade and a slice of bread take on the significance of a priest performing transubstantiation, while the use of a pack of playing cards in telling a fortune locates the ghoulish figures of her parents. What these private rituals appear to point to is an inversion of a Catholic funeral mass where, rather than marking a body for burial, Baglady is officiating the recovery and resurrection of her own lost sense of self.

abuse, Baglady snatches at any likeness that adequately reflects her own lost identity. Instead she’s met with monstrous apparitions of her father, her mother, and the priests and nuns who condemn her to a living death, bearing home the insidious ways in which abuse can find means of expression within its own victims. The simplicity of McGuinness’s stage images open up ritualized spaces for these figures to occupy: the introduction of a bottle of red lemonade and a slice of bread take on the significance of a priest performing transubstantiation, while the use of a pack of playing cards in telling a fortune locates the ghoulish figures of her parents. What these private rituals appear to point to is an inversion of a Catholic funeral mass where, rather than marking a body for burial, Baglady is officiating the recovery and resurrection of her own lost sense of self.

Certainly this is where McGuinness and Beckett part ways. While Beckett’s characters are prisoners of ritual, finding themselves ensnared time and again by a rehashing of the past, Baglady appears to be harnessing ritual as a means of escape and putting an end to the seemingly endless cycle of recriminations. But while there is the suggestion that a hint of hope is possible, even that sliver of assurance is achieved at the cost of an entire life tortured by history. Baglady’s final exhortation is, paradoxically, as much an acceptance of the past as it is a prayer for its erasure from memory.

Jesse Weaver