“There is not a better boy in heaven ...” These words were written not by a close relative of Thomas Andrews, chief designer of RMS Titanic, but by one of the hundreds of people, who were moved to send messages of condolence to the family after he went down with his ship in the North Atlantic a century ago.

This scholarly, minutely researched monologue play has been written by Belfast-born academic John Wilson Foster, who lived in the United States for many years. It is the second of Kabosh’s world premieres for the 2012 Titanic Belfast Festival and in form, content, presentation and style, it offers a striking contrast to Titans, Jimmy McAleavey’s intriguing, ritualised odyssey, which is simultaneously swaggering its way around the spectacular new Titanic Belfast signature building. Humble of scale and cosy of atmosphere, the creaky old Belfast Barge is acquiring quite a reputation for staging intimate, edgy performances and offers a nicely apt setting in which to eavesdrop on the musings of one of the city’s great shipbuilders.

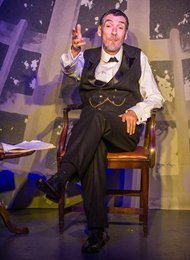

The central character is Lord Pirrie, chairman and managing director of Harland & Wolff at the time of the disaster whose name he cannot bring himself to speak. Pirrie, who joined the yard as a 15 year-old apprentice, may have risen to become one of Ireland’s wealthiest, most highly decorated and titled public figures, but in Lalor Roddy’s restrained, dignified performance, he remains essentially a plain speaking Belfast man, whose grating accent, sardonic sense of humour, unflinching work ethic and cold-eyed view of the world have never left him. But for all his shrewd business acumen and legendary powers of salesmanship, Pirrie’s number one priority was always his family.

The central character is Lord Pirrie, chairman and managing director of Harland & Wolff at the time of the disaster whose name he cannot bring himself to speak. Pirrie, who joined the yard as a 15 year-old apprentice, may have risen to become one of Ireland’s wealthiest, most highly decorated and titled public figures, but in Lalor Roddy’s restrained, dignified performance, he remains essentially a plain speaking Belfast man, whose grating accent, sardonic sense of humour, unflinching work ethic and cold-eyed view of the world have never left him. But for all his shrewd business acumen and legendary powers of salesmanship, Pirrie’s number one priority was always his family.

Through the focus of Paula McFetridge’s compact, tightly controlled little production, Pirrie presents himself at the height of his material success and at the lowest ebb of personal tragedy. The year is 1917, seven years before his death. He has been called upon to take wartime control of British merchant shipping and journalists are queuing up to talk to him about his remarkable life and career. For the past five years, he has remained tight-lipped about the shattering events of 15 April 1912 but now he breaks his silence by agreeing to an interview, as long as the subject matter is confined to his much-loved nephew Thomas Andrews, known to his family as Tommy.

A cautious, somewhat apprehensive Pirrie invites the interviewer to join him in the smoking room of his splendid mansion in the English countryside, Witley Park in Surrey. Glass of claret in hand, he settles himself reflectively beneath the magnificent dome of its opaque roof, around which water and weeds swirl. The effect is unsettling, disorientating, otherwordly, for the salon has been built under the estate’s lake, a queasy, but unremarked upon, irony.

His affection for his nephew is immediately evident and, initially, he seems content with reliving fond memories of Tommy’s privileged early years. Strings could have been pulled to smooth his path into the upper echelons of management, but Pirrie remains a man who has never believed in undeserved helping hands. He notes with satisfaction the sterling qualities, which rose to the surface in what was to be Andrews’s finest and darkest hour. But throughout this painful, sometimes heart-wrenching narrative, never once does he mention by name the ship which had been his pride and joy – the T word.

Bit by bit, Tommy’s shadow dims as Pirrie takes up a sheaf of closely written notes and embarks upon a soul-searching journey into his own past. Questions hang heavy in the air. Will he take ultimate responsibility for the disaster? Are we about to witness an admission of blame, of shame, of pride coming before a fall? Not a bit of it.

Foster’s densely packed text calls for total concentration from audience and actor alike. It is beautifully written, frank, uncompromising and fascinating in its personal insights and reminiscences. But, three parts of the way in, as Pirrie’s recollections of historical and political events escalate into a welter of detail, the speech rhythms in the text fleetingly become less fluid, less easy on the ear. And, correspondingly, one senses in Roddy a slight faltering in his, until now, flawless delivery.

Finally, Pirrie sets aside his notes and returns to his subject. Images of that dreadful night crowd in as he records the pain of the nightmare in which his nephew played such a heroic role. “Tommy tried to keep things shipshape to the end. He must have felt so alone,” he murmurs, as though to himself. Silence has settled over the capacity audience as Roddy, gaunt of face and dry of speech, quietly ends his story.

Jane Coyle is a Belfast-based freelance arts journalist, critic and screenwriter, who regularly contributes to The Irish Times, The Stage, Culture Northern Ireland and BBC Radio Ulster.