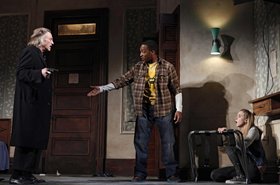

Premiered in New York, Martin McDonagh’s American play, A Behanding in Spokane, gives us a tall man in a tall tale. The tall man in question is the actor Christopher Walken whose stage presence is pivotal to this production’s success. The tall tale is the story of Carmichael (Walken), a self-styled white supremacist, who, when a child, had his hand held down by some “motherfucking hillbillies” until it was severed by a train, and who has been searching for the lost hand for forty-seven years. Two hapless pot-dealers, Toby (energetically played by Anthony Mackie) and Marilyn (a sometimes-shrill Zoe Kazan) offer him a stolen Aboriginal hand. The receptionist Mervyn (Sam Rockwell), noses his way into the hotel-room action, unwilling to assist the now-handcuffed pair because Toby has previously conned him. An eccentric maniac, Carmichael ultimately releases his captives after a phone conversation with his elderly mother in Spokane.

As with tall tales, it isn’t the tale’s implausibility that counts so much as the liveliness of the telling. What wins the audience are Walken’s performance and McDonagh’s mischievous play with language, his signature device.

The initial tableau establishes a key dynamic. A dingy American hotel room (designed by Scott Pask) features stained walls, iron radiators with exposed pipes, and a drab chenille bedspread, while outside the window glow large letters of a white-neon sign. The opening reveals a hulking Walken, legs wide, sitting center-stage on the edge of the bed, squarely facing us. The Broadway audience cheered at this celebrity sighting; some laughed, before a line was even delivered, at the familiar scenario. And this is the contract for the duration of the play: he will play a darkly-comic, articulate misfit (expectations already established in both Walken and McDonagh’s work), and we will come along for the ride.

Walken’s stage presence is compelling: he combines perfect comic timing with signs of menace (the flash of his trademark smile). The direction by John Crowley capitalizes on the character’s one-handed contortions. Carmichael awkwardly uses his mouth and remaining hand to construct a bomb from a candle and petrol can. Occasionally Walken’s uneven accent can be distracting, veering from Pacino bluster to a plummy mouthing of words, though such odd emphases arguably contribute to the character’s eccentricity. Other times it adds to the humour: “A reception-ist?” Carmichael spits at Mervyn.

The set-piece monologues provide the highlights of the script. During an extended phone conversation, Carmichael chastises his injured mother for climbing a tree to rescue a balloon and for snooping in his stash of porn magazines. Walken delivers this with superb pace and its relentless absurdity is hilarious. Sam Rockwell, as the know-it-all nerd Mervyn, delivers another of these extended riffs, in which he confides his drug-fuelled encounter with a gibbon. These are wonderfully written speeches, irresistibly pleasurable in their assimilation of random associations.

The set-piece monologues provide the highlights of the script. During an extended phone conversation, Carmichael chastises his injured mother for climbing a tree to rescue a balloon and for snooping in his stash of porn magazines. Walken delivers this with superb pace and its relentless absurdity is hilarious. Sam Rockwell, as the know-it-all nerd Mervyn, delivers another of these extended riffs, in which he confides his drug-fuelled encounter with a gibbon. These are wonderfully written speeches, irresistibly pleasurable in their assimilation of random associations.

Black humour tips into farce when, mid-play, Carmichael’s suitcase disgorges its contents of bloody hands. In an athletic piece of staging, Marilyn responds to the disclosure by literally scaling the wall in exaggerated recoil. Later these severed hands are hurled across the room, their rubbery texture bouncing off the walls.

Much of McDonagh’s theatre of the absurd rests on the pastiche of generic situations (a heist gone wrong) and characters (articulate maniac). In Behanding the absurdity is insistently textual: genres, conventions of speech, pop culture references. When Toby starts to question the credibility of Carmichael’s account of losing his hand, he cites the plot from a 1970s TV show: “I think I saw it in a movie with Lee Majors…or maybe I’m confusing it with the Bionic Man.”

The play’s strength lies in its self-aware language games. Mervyn confronts Carmichael about the scenario of overheard gunshots and missing guests, asking gleefully, “Where does a story like that go?” Carmichael answers for all of us: “We won’t know until you leave” (for when he exits, the plot recommences). Similarly, each time a character mixes a metaphor (“you’re barking down the wrong alley”), the dialogue plays on this, suspending the ‘action’, anticipating that we too have tripped on the mistake, before mining the linguistic implications. McDonagh has a keen sense of what catches the ear and he works this seam to comic effect.

The play with language extends to a virtual checklist of political-correctness issues: the “N word”, homophobia, PMS, old woman jokes. And McDonagh always beats us to it: “What’s up with the homophobia?” Marilyn asks, anticipating audience discomfort at the derogatory frequency of “fag”. The playwright mocks the audience’s knee-jerk reactions. In writing an American-based play, McDonagh has not, like his main character, “looked west, looked east” within that country, but has continued to flex his formidable linguistic muscles like a good postmodern-ist.

Heather Johnson teaches in the Writing and Rhetoric department at the University of Rhode Island.