On the launch day of the Abbey’s joint undertaking with NUI Galway to digitise its expansive archive, everybody seemed capable of making unusual associations. Some of these sounded like earnest topics for a PhD thesis, others sounded borderline facetious, but - with the theatre’s historical store ranging from programmes, scripts, photos and original prompt books to posters, designs, videos and company minute books – all of them now seemed much more possible to pursue.

The commercial relationship between Seán O’Casey and the Abbey, was one volunteered by the theatre’s Literary Manager, Aideen Howard, off the cuff, to illustrate how much data the 1.8 million items might encompass, or what a survey of box office receipts between 1904 and 1908 could yield.

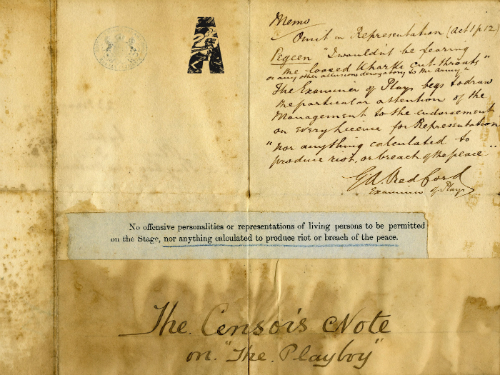

Dr Patrick Lonergan, from NUIG’s Theatre Department, wondered what might be revealed by a study of print advertising through Abbey production programmes, or what the evolution of bad language used in Abbey plays might say about us as a nation. The metadata that will be added to each scanned item, over a four-year digitisation process in Galway, will make everything instantaneously searchable. And while Mairéad Delaney, who for fifteen years has served as the Abbey’s archivist (its first), looked at a 1927 costume design for Eugene O’Neill’s The Emperor Jones – the pages singed at their edges from the theatre’s 1951 fire – she speculated about a hidden history of Irish blackface performance.

All the evidence for such investigations has long existed, but discovering it in the biggest theatre archive in Ireland – and perhaps the world – is no small task. The Abbey’s physical archive is so vast that even they don’t know its full extent. Visits are by appointment. At less busy times it can facilitate just one visitor a day. Some of the documents contained there are so fragile they would fall apart like confetti in your hands. Digitisation, then, is an act of duplication, of preservation and – even though availability will be restricted to NUIG staff and students – of providing much greater access. This will certainly make research easier, but making interesting connections out of the material will still require specialism and patience.

All the evidence for such investigations has long existed, but discovering it in the biggest theatre archive in Ireland – and perhaps the world – is no small task. The Abbey’s physical archive is so vast that even they don’t know its full extent. Visits are by appointment. At less busy times it can facilitate just one visitor a day. Some of the documents contained there are so fragile they would fall apart like confetti in your hands. Digitisation, then, is an act of duplication, of preservation and – even though availability will be restricted to NUIG staff and students – of providing much greater access. This will certainly make research easier, but making interesting connections out of the material will still require specialism and patience.

According to Lonergan, the partnership behind the project was created using distinctly analogue methods; namely chance remarks during physical meetings. Eighteen months ago, during the Theatre Forum conference in Galway, the idea became inchoate, and NUIG suggested it played to two of the university’s strengths: its Irish theatre scholarship and its burgeoning facility for digital humanities – the use of computer technology to better understand culture. The Digital Abbey Archive, which will be housed in NUIG’s new Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences Research facility, itself due for completion next year, joins several other Theatre collections at the James Hardiman library, among them the papers of Thomas Kilroy and the Shields Family Collection and the archives of Druid Theatre, Taibhdhearc na Gaillimhe and the Lyric Players in Belfast.

The cost of the digitisation, for which all material must be transported to Galway, has not been revealed owing to “commercial sensitivities”, nor any details of how those costs are being funded or split between the university and the theatre. The likelihood, though, is that both parties recognise quid pro quo gains: the Abbey will always retain rights to its archive, NUIG will become the first port of call for Abbey scholars while anticipating an increase in visiting scholars (a lucrative business in economically-straitened times) while also creating new funded PhDs for researching the archive, and both organisations will receive a copy of the complete digital archive.

A mention in one press release suggests a finite 25-year contract with NUIG as exclusive holders of the Abbey’s digital archive: “133 years of Irish theatre, history, culture and society preserved for future generations (1904-2037)”. Proprietorship, in the age of digital reproduction, is a hot topic. The material clearly has great value and with the Abbey finding income streams from various divisions, from Development to Costume rentals, the idea of making this material available online for free may seem like an altruistic fantasy.

“Long term we’d like as many people to have access to it as possible,” Lonergan told ITM, “but obviously there are issues of copyright as well. You can’t make plays that are still in copyright available for free.”

Howard said that they had considered providing free access to the archive at some point in the future, “but I don’t think we’re quite there yet. We’d like to know our business a little bit better, with the help of scholars, before unleashing that wholesale into the world.” Instead, NUIG will curate a series of online exhibitions from the material which will be available to the public.

True to the philosophy of the digital age, everything must be saved and nothing deleted. The physical archive, as it may soon come to be known, will continue to function as it always has. “I’m not sure that [the digital archive] will supplant it,” said Howard, “but I hope it will act as a filter in many ways. The real material will always be so precious and so exciting to see and touch and look at; for example, the Synge Prompt Book.” Delaney felt similarly and admitted that accidental discoveries, through visits and conversations, happened all the time. “That would still happen because the main collection will still be in the Abbey. A certain generation don’t want to look at the digital [replica], they may want to look at the original. At least they still can. But they can have an awareness of what’s there first before they come.”

It was also hoped they could increase their understanding of a whole theatre culture beyond texts and artefacts. “We hope all these records will represent a much broader picture of how theatre is actually made,” Howard told a media gathering, asserting the centrality of the writer within the Irish theatre, but adding, “We hope that by making this material more available in all kinds of detail, scholars will be able to think of theatre as a more broadly collaborative artform.”

That was also Lonergan’s interpretation. “This will revolutionise the study of Irish theatre.”

A visitor in the Abbey that morning might have observed Seán O’Casey’s original prompt copy of The Plough and the Stars and wondered about the limits of digitisation. In the book, now safely kept under glass, the playwright had pasted Nora Clitheroe’s song over an older version which had never performed or published. The original was still detectable, with some effort, to the eye, and it hinted at further secrets within the play – why the character was called “red-lipped”, for instance. Whether a sophisticated scanner can read below the surface, or, for that matter, between the lines, we’ll soon find out. Now, however, scholars will know precisely where to look.

Peter Crawley is News Editor of Irish Theatre Magazine