Choreographic primers used to be dull enough reads. Compulsory reading for unimaginatively titled courses, like Dance Composition, they rarely led aspiring choreographers to greatness (although their building-block approach helped many uninspired dancers to scrape through an obligatory course in choreography). There was also a closed-shop devotion to each author, so those who adored Doris Humphrey's The Art of Making Dances would more than likely be advocates of Humphrey-Limon technique and wouldn't dream of reading what Erick Hawkins might have to say about the act of choreography.

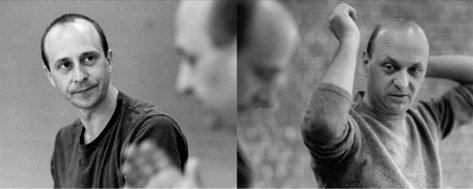

Jonathan Burrows, who will appear during this year's Dublin Dance Festival, has written A Choreographer's Handbook. It's a much broader text, not just in the aesthetic vision it suggests, but in its range of content that includes observations on funding applications, nudity and set design.

“I decided to try and write A Choreographer's Handbook to reflect the multiplicity of ways dance artists now work, because there wasn't such a book written by an artist for younger people coming into the scene,” he says. “It was a risk because I don't assume I know everything, but I used notes taken from a long series of workshops I'd led with other choreographers and dancers, and I used these to underpin and counteract my own ideas.”

His directions are decidedly guide-on-the-side rather than sage-on-the-stage. Instead of listing essential truths, he is open-palmed about the slippery process of choreography. On page one he writes, “We usually don't know what we are doing.” It's a surprising way to begin a handbook, but a very deliberate statement.

“In Dublin [composer] Matteo [Fargion] and I will show two of the four duets we've made which are an ongoing conversation and critique of the ideas of John Cage, and specifically his 'Lecture On Nothing'. The first of the pieces is Cheap Lecture, which borrows the shape of the Cage and sometimes echoes things he wrote. 'Lecture On Nothing' begins with the famous statement 'I am here, and there is nothing to say', which we translated as 'We don't know what we're doing and we're doing it.' Our version reflects the discovery that powerful images often arrive by letting go the desire to express, and that even then you usually don't recognise them until later.”

With such ambiguity how does he answer the question that is usually first to pop up at post-show discussions: what is your process?

“The difficulty when you talk about process is that some of the ways you work become familiar so that you stop noticing and don't talk about them, and the things you can talk about start to sound rather codified and stiff. There's always this balance between what you think you're doing and the more hidden layers of activity underneath, which are less stable and can't be rationalised in quite the same way.”

An important common ground between himself and Fargion is music. Both studied music composition with composer Kevin Volans, a South African-native, now an Irish citizen living in Cork.

“Music is what we make, though [it is] expanded to include first dance and then text, objects, projections and so forth, and always clashed against the idea of performance itself. We begin with an idea, usually some unfinished business from an old attempt to work, and then we approach this idea through the writing of a score as in a piece of classical music. The purpose of the score is to give a bit of distance so we can see what we're doing, and to look after some of the detailed decisions and allow us to become more free to be intuitive in others.”

Those with long memories who saw Burrows and Fargion in Both Sitting Duet at the 2004 Dublin Dance Festival, might remember them reading from their scores on the floor, but this years performance will feature a far messier finale: “Do say hello if you come by the show. We're usually onstage at the end picking up score papers we've throw on the floor,” Burrows says.

Those with long memories who saw Burrows and Fargion in Both Sitting Duet at the 2004 Dublin Dance Festival, might remember them reading from their scores on the floor, but this years performance will feature a far messier finale: “Do say hello if you come by the show. We're usually onstage at the end picking up score papers we've throw on the floor,” Burrows says.

Dance scores, books, notebooks all suggest that the act of writing is an important part of his aesthetic make-up. Both choreography and writing seem entwined in one creative flow. He approached writing his book in the same way he'd approach a piece of choreography so that the things he was writing about were reflected in the way the book itself was laid out.

“The most obvious thing A Choreographer's Handbook has in common with the performances I make is that it's built of short blocks of text which inter-relate, and some of them repeat at various moments in an almost rhythmic way.”

Similarly, when talking about stage collaborations with Fargion he says: “We've become more and more interested in the relationship between things and the way meaning often arises and accumulates in the gaps between one thing and the next, so that everything is altered by what it stands next to or even what has come before or will happen in the future. It's more how a poet works, not necessarily deciding a subject before starting but rather writing to find it.”

That sounds just like writing “we usually don't know what we are doing” on page one of a book.

The physical act of writing, although not a formal part of his choreographic process, does help him clarify his ideas and structure. “I do enjoy laying out and editing the score of the performances as we make them, which has a quite calming effect and allows you to meditate a bit on the piece as it unfolds." Writing his book was an act of discovery, as he read through twenty years of notebooks from making work and teaching.

“I dreaded doing it, but it became a very interesting kind of research, discovering the threads of ideas and how they developed or petered out over the years. In the end, I realised that I was writing partly to empty the cupboard so that I could start again, and the process has made some space for new perspectives that I maybe couldn't have arrived at while I was still holding tight to old and cherished notions.”

Old and cherished notions suggest calcified ideas, but nowhere in Burrows' work – onstage or in print – is there a hint of an aesthetic cruise control. Ideas are restlessly explored with insatiable curiosity. And audiences have responded in kind. Sometimes his work is greeted with chin-stroking silence, at other times with mirthful laughter. So how does he deal with the tension between clarity and ambiguity in his work?

“Well this is a really interes ting question and one that gets to the heart of current dance practice, because we're in a period where clarity of concept is predominant and sometimes at the expense of more ambiguous poetics, and yet the striving for clarity has produced some marvellous work.

ting question and one that gets to the heart of current dance practice, because we're in a period where clarity of concept is predominant and sometimes at the expense of more ambiguous poetics, and yet the striving for clarity has produced some marvellous work.

“The problem is it's very difficult to articulate why a dance has moved you, and that quality is both wonderful and frustrating. It's the reason many people come out of a dance performance and say, 'I liked that, but I didn't really understand it'. Matteo and I strive for the clarity of shape and tone that you find in music, which accepts also at times a more lyrical and perhaps ambiguous approach. And because we work a lot with setting up and breaking expectations it gets hard sometimes to avoid the absurd, which might seem ambiguous or not depending on who you are and how you're feeling.

“So I'd say that ambiguity is a powerful tool but you must never take it for granted, it always has to balanced against the attempt to be clear about what you're saying and why you're saying it.”

Michael Seaver is dance critic with The Irish Times, and a musician.