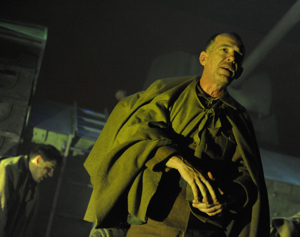

The day after the EU-IMF bailout was announced, I went to see Performance Corporation’s Slattery’s Sago Saga, which was playing for one night only at the Town Hall Theatre in Galway. It’s an adaptation by Arthur Riordan of an unfinished Flann O’Brien novel and, as you’d expect from both authors, it is very, very clever – and completely mad.

Yet it also seemed surprisingly topical – almost prescient, in fact. The idea at the centre of the plot (such as it is) is that acres of Irish land are being bought up by a foreign power – someone who claims to be acting in Ireland’s national interest, but who is in reality determined to wreck the country for her own ends. Her dreadful schemes are aided by the local gombeen politician, who happily sells away Irish independence in exchange for personal enrichment.

Added to this story is a barmy metatheatrical subplot, in which all the characters gradually realise that they’re not real people, but are actually themselves characters in a play – a truly atrocious play, being written in “real” time by a mysterious author figure.

Sitting at home afterwards, I watched TV interviews with Ajai Chopra, Brian Lenihan, and many others. And it seemed like Slattery’s Sago Saga had already said everything that needed to be said. The play was telling us something about the loss of sovereignty – about the politicians we elected, about the lies we told ourselves. And it was also giving us a marvellous metaphor for the way we live now. After all, to be an Irish citizen today feels exactly like being trapped in a bizarre drama – one where we’re helpless to do anything except follow a script being improvised by an incompetent lunatic.

So, to repeat one of the year’s most overused buzzwords, Slattery’s Sago Saga (pictured) was “relevant”. What’s important, though, is that its resonance on that one night in Galway was completely unplanned, completely accidental. In fact, the real value of the play is that it placed our current problems into a broader context: it showed that the dementia from which we suffer today existed before – in the 1950s, in the1920s, in the 1840s. So it reminds us of the crucial difference between art and journalism. Journalism is relevant because it looks at the present; art is relevant because it transcends the present, to reveal the deeper patterns that explain our lives – our strengths, our mistakes, our blindspots, and our hopes.

So, to repeat one of the year’s most overused buzzwords, Slattery’s Sago Saga (pictured) was “relevant”. What’s important, though, is that its resonance on that one night in Galway was completely unplanned, completely accidental. In fact, the real value of the play is that it placed our current problems into a broader context: it showed that the dementia from which we suffer today existed before – in the 1950s, in the1920s, in the 1840s. So it reminds us of the crucial difference between art and journalism. Journalism is relevant because it looks at the present; art is relevant because it transcends the present, to reveal the deeper patterns that explain our lives – our strengths, our mistakes, our blindspots, and our hopes.

This, it seemed to me, is a distinction that was sometimes lost in 2010: instead of attempting only to be interesting, companies sometimes tried a little too hard to be relevant – and in doing so may have blurred the lines between art and journalism.

This is not to say that such plays were bad. I greatly enjoyed Simon Doyle’s Off Plan for RAW productions, for example, but felt that the conflation of Irish property development with Greek tragedy exaggerated the significance of our own grubby collapse. Rough Magic’s Phaedra was similarly a little too bound to our present – but when it moved into the universal (which it achieved mainly through the fusion of Ellen Cranitch’s score with Hilary Fannin’s script), it was one of the year’s most absorbing plays. Only Selina Cartmell’s Medea got the balance fully right, I thought: she avoided explicit references to the present, and in doing so allowed the audience to establish the play’s relevance to their lives for themselves.

One of the most interesting examples of this confusion was, for me, the Abbey’s production of John Gabriel Borkman, adapted from Ibsen’s original by Frank McGuinness. The excellence of its production values was immediately impressive. In casting Alan Rickman, Lindsay Duncan and Fiona Shaw in a play bound for New York, the Abbey were making a very powerful assertion. They were showing convincingly that they can do work every bit as impressive as the recent British imports to New York, from theatres like the Donmar Warehouse and Old Vic. And indeed, it needs to be stated that the Abbey in 2010 had its most impressive year in a very long time: there was an admirable consistency of achievement, and an openness to other companies, that made a very positive impact.

Yet, curiously, the Abbey’s marketing of Borkman as “fiercely relevant” actually inhibited its reception, at least for me. We were faced with the figure of a disgraced banker, and I never knew whether to laugh at him, hate him, or pity him – and in the end felt little other than admiration for the acting of Rickman. Similarly, in a thoughtful Guardian blog, Mark Fisher wondered about the appropriateness of the laughter that was generated by Borkman. Whatever its merits, Ibsen’s play doesn’t tell us much about banking, or money, or how we can live in a society that is facing a serious crisis. If the intention was to present a classic that would be “fiercely relevant” perhaps something like The Merchant of Venice might have been a better choice, dealing (as it does) with the consequences that arise when foolish people borrow money that can’t easily be repaid – a play, that is, that warns us not to scapegoat the money-lender until we’ve considered our own responsibilities.

Yet, curiously, the Abbey’s marketing of Borkman as “fiercely relevant” actually inhibited its reception, at least for me. We were faced with the figure of a disgraced banker, and I never knew whether to laugh at him, hate him, or pity him – and in the end felt little other than admiration for the acting of Rickman. Similarly, in a thoughtful Guardian blog, Mark Fisher wondered about the appropriateness of the laughter that was generated by Borkman. Whatever its merits, Ibsen’s play doesn’t tell us much about banking, or money, or how we can live in a society that is facing a serious crisis. If the intention was to present a classic that would be “fiercely relevant” perhaps something like The Merchant of Venice might have been a better choice, dealing (as it does) with the consequences that arise when foolish people borrow money that can’t easily be repaid – a play, that is, that warns us not to scapegoat the money-lender until we’ve considered our own responsibilities.

On the surface, then, Borkman was as well produced as anything you’d see internationally. And, on the surface, it was registering our sense of outrage for the collapse of our economy. But at its heart was an uncertainty – about who was being addressed, what was being said, who was being blamed, and whether the play would be understood. I found that lack of direction (that lack of confidence, perhaps) both sad and compelling. And, again, it was very "relevant", but not for the intended reasons. Like Slattery’s Sago Saga, Borkman seemed like an accidental metaphor for Ireland today: capable of achieving great things, but unsure of its core values and identity.

In contrast with such uncertainty, the younger people in Irish theatre often seemed supremely confident about who they are and what they’re doing. Director Wayne Jordan had a great year, especially at the Abbey (which showed real vision in giving him two mainstage productions). But there were so many other exciting individuals and companies around the country. The work of Louise Lowe is especially promising, displaying a genuine intellectual daring, and a determination to do difficult things well. Grace Dyas showed a very appealing ability to present innovative work – and also to write about it with depth and clarity (something we really need right now, from everyone involved in Irish theatre). At the Galway Theatre Festival in October, I saw inventive and surprising work by several emerging companies. And this year’s Absolut Fringe festival was, by common consensus, the best yet.

Much of that work dealt with the economic crisis – not by addressing it directly, but by showing a refusal to be cowed by our present circumstances, a determination to be excellent and to ask daring questions. I found such work consistently inspiring.

Perhaps the best plays of 2010 were inspiring precisely because of their excellence, because of their insistence that we keep going. Enda Walsh’s Penelope gave us four men who, facing certain death, choose to give the best performances of their lives. Dermot Bolger’s The Parting Glass presents a character who faces horrendous adversity by saying that he’s only reached “half-time” in the football match that is his life – that it’s all still to play for. Druid’s Silver Tassie (pictured) reminded us that people will persevere under the worst circumstances – but reminded us too that our determination to carry on can sometimes cause us to leave others behind. And the Gate presented Owen Roe as Frank Hardy and Michael Gambon as Krapp. Both gave brilliant portrayals of people who persist, even in the face of death, but as actors both also showed an attention to detail – a care about excellence – that was exemplary in the widest possible sense.

Perhaps the best plays of 2010 were inspiring precisely because of their excellence, because of their insistence that we keep going. Enda Walsh’s Penelope gave us four men who, facing certain death, choose to give the best performances of their lives. Dermot Bolger’s The Parting Glass presents a character who faces horrendous adversity by saying that he’s only reached “half-time” in the football match that is his life – that it’s all still to play for. Druid’s Silver Tassie (pictured) reminded us that people will persevere under the worst circumstances – but reminded us too that our determination to carry on can sometimes cause us to leave others behind. And the Gate presented Owen Roe as Frank Hardy and Michael Gambon as Krapp. Both gave brilliant portrayals of people who persist, even in the face of death, but as actors both also showed an attention to detail – a care about excellence – that was exemplary in the widest possible sense.

Few of those works were explicitly topical – but they all did something immensely important. They fortified us, reminding us that we can keep going even when everything seems hopeless.

For all of those reasons, the play that best sums up the year is Thomas Kilroy’s Christ Deliver Us at the Abbey. Like many important recent works (Freefall, The Last Days of a Reluctant Tyrant), the play suggests that, whatever our economic situation, the guilt we must feel as a society in the wake of the Ryan Report needs to be addressed too. Kilroy shows us something that’s difficult to accept: that the abuse experienced by people in Catholic institutions was made possible by the silence – and occasionally by the malice – of entire communities. This, it seemed to me, was our national theatre at its bravest: demanding that we forgive others and consider instead our own culpability. So, instead of giving us a message or a sound-bite, it gave us something much more valuable: ideas to consider.

Among the many things that Kilroy achieves in his play is to show how play – theatricality – acts as a subversive force within repressive environments. In one particularly moving scene, brilliantly directed by Wayne Jordan, Kilroy presents two boys dancing with each other. They move around the stage with fluidity and grace: one boy runs towards the other; he is caught and held in the air, before being flung down in a gesture that’s full of a playful arrogance. They then repeat the movement, swapping roles: they move towards each other, and kiss, tenderly. Then someone sees them: they run away and aren’t seen again. They are an unsolved mystery at the heart of the play.

Like so many of the great dances in Irish drama, Kilroy’s scene shows how movement offers a form of expression for people who were denied the ability to speak or be spoken about openly in our society. And he reminds us too that desire, affection, grace – and indeed love – can persevere under the worst circumstances. And he shows us, finally, that all of those things can best be revealed through play, through performance.

I can think of no better example of the value of Irish theatre, no better example of how the relevance of art arises from its permanence rather than its topicality. It’s probably worth recalling in this context that Kilroy wrote Christ Deliver Us years ago – long before the Ryan Report appeared: again, the topicality of the play was accidental.

Especially important is the play’s conclusion, which involves an appeal for us not to repeat the mistakes that have brought us to where we are now. “Know nothing!” says one of the characters. “Ignorance is the start of everything… That’s what drives us forward. Questions. Always questions. We are born under the sign of a question-mark… And that’s how we end too. Questions, questions!”

This finale is extraordinarily powerful. At its best, our theatre articulates the kinds of values that we can use as a society as we attempt to move on. Kilroy refuses to allow us to deny the awful pain that has been caused and experienced in Ireland over many decades. But he also reveals that we have found ourselves in a moment of opportunity. The loss of certainty leaves us in a state of ignorance – but that ignorance can be the occasion of questioning – and questioning is the foundation of all creativity.

As Kilroy shows, such questions have to be informed by knowledge of the past, and we have to take and be given the time and space to consider them carefully. And we also need to remember that sometimes it’s enough just to ask a question: we don’t always need to rush to provide answers, for ourselves or other people.

Christ Deliver Us, then, doesn’t tell us how to move forward – but it does something that encapsulates perfectly the achievement of Irish theatre during 2010. It helps us to imagine that we can move forward.

Patrick Lonergan lectures at NUI Galway. His collection of essays Synge and Modern Irish Drama will be published in early 2011, and he is writing a book about Martin McDonagh’s plays and films, which will be published by Methuen Drama in 2012.

And in our end-of-year review series, read Peter Crawley: The Year of Living Differently